Listening to 1984: The Final Chapter

A lot changes when you spend three years of your life living through one year that originally took place about four decades back. (I know, I know... I'm confused too!)

The story so far: Sometime in 2019, I had a premonition that 2020 was going to suck. So— I decided to spend the year re-experiencing my favorite year from my childhood: 1984. By "re-experiencing" I mean listening to the music, watching the TV shows and movies, reading the news magazines and books, and listening to "American Top 40" and "Newsweek on Air" week-in, week-out, in chronological order. Weirdness ensued. I kept a journal. It took longer than expected, and by the spring of 2022 I was still in 1984…

(Note: If you just came onboard and are thoroughly confused, start with Part 1.)

December 1, 1984 / April 5, 2022

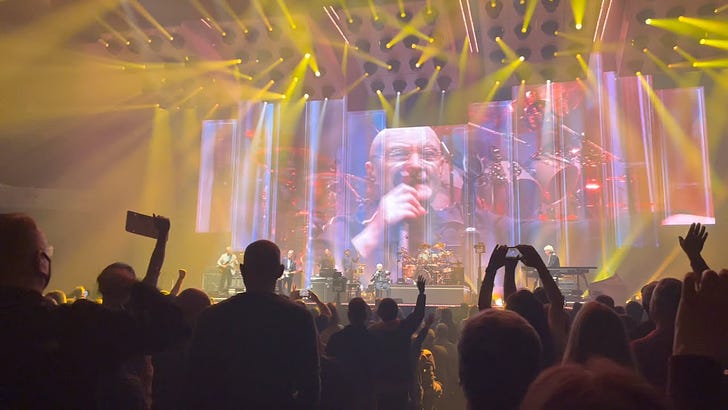

In 2022 an ailing Phil Collins has performed what he says will be his final concert. Fittingly it is with Genesis, the band that first brought him to public attention. In our parallel timestream of 1984, Phil is hale and hearty, riding high from the back-to-back successes of the Genesis single “That’s All” and the solo #1 smash “Against All Odds.” “Easy Lover” (with Philip Bailey) is soon to ascend the charts. He is the de facto house band for Miami Vice, and the monster album No Jacket Required is not far off.

In 2022, his body is falling apart, his face drawing in on itself. His voice wavers precariously and he needs the assistance of a cane to make his way onstage. This tsunami of health issues is apparently the result (partially at least) of a lifetime of ferocious drumming. Could there be a starker exhibit of the ravages of time, or the distance between here and 1984?

The most moving part of Genesis’ “The Last Domino?” tour, which my wife and I attended in Charlotte in 2021, was a video montage of ‘80s-‘90s (and earlier) footage of the band, which served as the backdrop for their performance of the 1986 single “Throwing it All Away.” The images played out on the magnified “spines” of cassette tapes—a ubiquitous symbol of the 1980s if ever there was one. Phil faltered and forgot lyrics, but the audience carried him. Certain lines hit viscerally:

“I don’t want to be sitting here trying to deceive you / Cause you know I know baby, that I don’t wanna go.”

That sense of loss, of regret, of being unable to continue, permeated the Genesis performance—an undertow to the beauty of the music. But who am I kidding, it’s the reason for the beauty, intertwined with the melody lines like the strands of a DNA helix. For whatever reason, lasting love has eluded Phil Collins. And that absence has served as the rocket fuel for his spectacular success—which, in turn, produced a spectacular backlash. It is only now, at the very end, that people (critical tastemakers especially) are beginning to grasp his contribution to music. So many of us got distracted by his Vaudeville-inflected stage persona, his sometime lack of editorial discernment, his ubiquity—seemingly everywhere in the charts for what seemed an interminable period of years. At his best he was anything but bland—a true innovator in fact—yet he came to represent a middle-of-the-road sensibility that was easy to dismiss or mock. Now he has left the stage and I doubt anyone will fill the void.

December 5, 1984 / May 3, 2022

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) vs 2010: The Year We Make Contact (1984).

Two films very much of their times.

2001: Austere, psychedelic, subtle. Lots of open space—in the script, in the execution. Maddeningly ambiguous.

2010: Compulsively tries to explain everything. (Do we really need the voiceover?) It is a movie at war with its own intelligence—a movie that surrenders to the Hollywood need for hammer strokes when a paint brush would be more appropriate. And yet, I sense that Arthur C. Clarke, author of the underlying material, was going for something different, something still of the 1980s but not quite so obvious. The movie can’t completely fail because that material is smart and interesting.

Again, there are ripples in the timestreams—although now we have four timestreams in play: 1984, 2022, the real 2010, and the fictitious 2010 depicted in the movie. In three of the four (with the real 2010 arguably the exception), we find the US and Russia at an impasse with communications breaking down and the potential for escalation growing. 2010 captures the feeling of hopelessness in the face of such a challenge.

What else have we learned? Apparently, HAL was misunderstood. You see, it was just a conflict in his programming: There was his “scientific mission” and there was another set of orders from the White House, and he was unable to reconcile the two. Mayhem ensued.

My sixteen-year stint in the tech sector leads me to reject this explanation. It’s more likely that HAL was buggy, like any beta release. Or maybe a Windows update broke the thing. And now we have this revisionist take, which tells us we should not be wary of technology, or its harried developers and QA departments, and that it’s solely the military (and government power behind it) to be feared. Well, how about this: We ought to be suspicious of both the tech industry and the military-industrial complex.

This sequel is both fascinating and disappointing. On the one hand, it’s warmer than 2001, with better-developed characters. And it wisely does not attempt to emulate the style of its predecessor. But it’s also a smaller movie—not smaller as in more intimate (though intimacy is one of its strengths)—but as in more pedestrian. I’m intrigued enough that I’d like to read Arthur C. Clarke’s novel, but I’m not sure if the movie should have happened.

Also debuting on this date: Beverly Hills Cop. What can I possibly add to the public record about this action-comedy juggernaut?

Eddie Murphy, with his frenetic delivery and quick emotional pivots, owns it from the first frame—due in no small part to director Martin Brest’s ability to yoke Murphy’s unconventional comedic talents to a fairly conventional fish-out-of-water plot. It’s an instantly appealing mix, relentlessly paced. I’m not surprised to learn that it was the highest grossing movie of 1984, and I remember that somehow, everyone but me managed to see it in 5th grade. Plus the theme song “Axel F” was everywhere.

So many times this year I’ve watched icons fully come into themselves and own their moment: Madonna, Prince, Cyndi Lauper, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Don Johnson. It truly is the “beginning of everything.”

December 14, 1984 / January 9, 2022

This is a significant date in movies: Dune, Starman, Mass Appeal (a favorite of my parents) and 1984 itself: brooding, claustrophobic, boasting a Eurythmics soundtrack and John Hurt at his best. It’s good—or at least it sounds good. (I’m listening to it as I go on my daily walks.) I just imagine the visuals from Ridley’s Scott’s Macintosh commercial earlier in the year and I’m set.

A lot changes when you spend three years of your life living through one year that originally took place about four decades back. (Now that is a tortured sentence if I’ve ever read one, but how else to put it?) I’m writing these words in 2022 on a plane just beginning to taxi down the runway—bound for Myrtle Beach, SC, with Wilmington NC once again our final destination. This is our third annual migration, and each of the trips has been radically different. In 2020 it was the kids and me on a half-empty plane just days after the lockdown began. No one was seriously considering mask mandates at that point; the consensus was that you got Covid by rubbing your eyes. The preventative recommendations were hand sanitizer, “social distancing,” and “shelter in place.”

The following year, we made our journey via car. There was a feeling that the pandemic—now known to be transmitted via airborne particles—was ending; the CDC had even rescinded its mask mandate. Three months later the Delta variant was in swing and health officials reversed course.

Throughout it all, there were crises on the macro level: riots, insurrection, culture wars, the ever-present natural calamities and human atrocities. On the micro level, we were roiled by discord and loss within my wife’s family. Meanwhile, in my alternate reality, Mondale and Reagan duked it out for—three years? I’ll say it again: Time bends, stretches, folds back on itself. The past punches through to the present and vice versa. This fun little project has turned into a wearying and disorienting burden. Even so, it has been an extraordinary experience.

As for the 1984 movie version of Orwell’s 1984, well, it is at the very least a brilliant radio drama. John Hurt’s presence ensures a base level of quality, plus we have Richard Burton—my grandfather’s favorite actor—in his final role. It’s got a Eurythmics record burbling through it; maybe some people think that sounds dated, but to me it’s still the sound of the future.

Everyone seems to think that the story of 1984 is about them. I would guess that lefties watching 1984 in 1984 thought of the cult of Reagan, with the seemingly neverending Cold War as analogous to the book’s/movie’s staged war between Oceania, Eurasia, and Eastasia—a nonsensical conflict whose sole purpose seems to be distraction, manipulation, and subordination of the populace. Those on the right would have found parallels between the story’s “Big Brother” surveillance society and the then-current regimes in Moscow and Beijing.

In 2022 the book tracks eerily with the pandemic and is invoked by conservatives aiming to critique cancel culture and top-down social engineering. But it was also invoked by the left when Trump came to power.

What’s certain is that no one has a monopoly on tyranny. And no one—it seems—can quite grasp or hold onto freedom. Elon Musk wants to make Twitter a haven for free speech. But will it be a haven for the stimulating exchange of ideas, or will it be a metastasized 4chan? I mean, it’s freaking Twitter so I’m not holding out hope.

Is freedom from control possible? Is it desirable? Absolute freedom from all constraints seems to herald a yawning chasm of madness, emptiness, and loneliness. The technology critic Jaques Ellul, who described himself as “pretty close to being a libertarian,” nevertheless defined freedom as submission to the will of God (or Christ in Ellul’s specific formulation). Once you surrender to this higher power, Ellul contended, you are freed from a million confusing and contradictory choices and impulses. If, as Bob Dylan asserted, you “Gotta Serve Somebody” (“It may be the Devil, or it may be the Lord, but you’re gonna to have to serve somebody”) then God may be the best option available.

Ayn Rand broke free of a tyrannical communist state and promptly created an “Objectivist” movement that tyrannically purged its heretics. Libertarians valiantly resist state control but some wax poetic, with apparently no sense of irony, about “the movement.” (Could a true libertarian be part of a movement?)

Can we be free from impossible causes? From that “long march” toward some sort of ever-distant utopia that was described so devastatingly in Milan Kundera’s 1984 novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being? Paradox upon paradox. But I can’t stop trying to get free, and a voice inside me says that Orwell’s 1984 is the most important novel ever written (and its 1984 movie adaptation a fine effort with its own resonances). In my life it was 1984 (the book) plus Emerson plus Thoreau that set the course for everything that followed. All three were introduced to me by Catholic educators. The combined result was my abandonment of Catholicism.

****

Hot take on David Lynch’s Dune: Do these Atreides folks brush their teeth, use the bathroom, and buy groceries in the midst of all this prophecy and portentousness?

I have been watching an extended fan cut (“The Spicediver Edit”) which is compelling. The fatal flaw, which no editing can fix, is the bombastic obese villain who floats around yelling out his master plan.

It’s got Sting, so in that sense it’s a 1984 movie. But otherwise, its mysticism and “big ideas” are rooted in the 1960s—the era that produced the novel. Needless to say, Dune baffled audiences in 1984 and followed its giant worm right back into the sands of oblivion.

I do recall some teacher-led discussion in my fifth grade classroom of the Dune books and movie. Our talk centered on the idea of a desert planet, on which water was a precious and rationed resource. There was no mention of the spice melange—clearly based on psychedelic drugs. Makes me wonder: In the far-flung galactic empire of Dune, are there citizens’ groups worried about peoples’ growing dependence on the spice? Are there breakaway societies who have opted out of the scheme? Are there political pressures for the central government to not be so dependent on Arrakis? Clearly the cartels are a problem.

*****

In 2022, my wife and I watch Top Gun: Maverick, an enjoyable fantasy swaddled in ‘80s nostalgia. Josh Rouse’s line immediately springs to mind: “It’s times like these when I’m alone / I miss the iron curtain.” In the alternate reality of Maverick, the U.S. is at war with some undefined “enemy” that is getting ahead of our combat technology but doesn’t yet have nuclear capability. This ticks a lot of ‘80s boxes: a comfortable Cold War-style parity with potential for some aerial dogfights here and there but none of the horrors of actual ground or nuclear war. In such a world, there is apparently a need to continue the money-guzzling “Top Gun” program because… you never know when you’re going to need to fly a bunch of planes through a Star Wars-style trench, fire some rockets into a target the size of an Amazon delivery box, and vault into the heavens at Mach 10.

Preposterous. But soothing as a warm blanket—the future as we would have imagined it in the 1980s.

December 21, 1984 / July 29, 2022

A curious observation as I near the end of this experience: At this point, many of my memories of 1984 did not take place in 1984; they’re from 2020-2022: those epic walks around the Wrightsville Beach loop during the pandemic, and later through the midtown neighborhood of our Wilmington Air BnB, listening to Cheers, Magnum P.I., Hill Street Blues, and all those intriguing movies from the first half of the year like Moscow on the Hudson and Paul Newman’s Harry and Son. Yes, I have a memory of seeing Ghostbusters in 1984, but it now has to compete with the memory of listening to Ghostbusters while driving through the Colorado mountains during a work trip in 2020. For me, forevermore, 1984 occurred twice; during 1984 and then again, during the second half of my forties.

December 21, 1984 / August 13, 2022

Alison Lurie’s Pulitzer-winning 1984 novel Foreign Affairs, detailing the entanglements of three American tourists in the UK and their equally rudderless English counterparts, is beautiful, subtle, perceptive, superficially breezy yet harboring great depths. It cuts against the grain of such a “big” year.

In the end, our protagonist, the aging American academic Vinnie Miner, is a better person than she takes herself to be. She is often tempted toward the petty, the casually cruel, but she often takes the high road (though she is never quite sure why she’s doing so). She has a breakthrough at the end, emerging from her embarrassment and her desire to keep up with the Joneses to declare that she loved the uncouth, unschooled Chuck Mumpson—her painfully American fellow tourist with whom she had fallen into an improbable affair. The world bursts into color as her inside and outside selves come into alignment. But it lasts all of a minute before her insecurities pull the ascending phoenix back down into its flames.

Vinnie’s fellow tourist (and fellow academic) Fred Turner is something less than he imagines himself to be. For one moment, the scales fall from his eyes and he can’t bear it. But it passes; his overconfidence, his moral blinders snap back into place as a matter of self-preservation.

We can read this as a commentary on American hubris in the 1980s—the microcosm of these Americans fumbling around and wrecking things as a stand-in for the geopolitics of the age. We can—but I won’t. I think Alison was up to something more subtle and generous here.

We could also say that the book’s examination of selfishness ties in with the spirit of the 1980s—that is, if we (and Alison) buy into the idea of the ‘80s being the “me decade.” Certainly there was truth to that impression of the era, and it could very well have been the author’s intent to highlight it; but at this point, in the 2020s, do we have any right to call the 1980s out? The ‘80s now appear markedly less selfish than our current time. How could anything in 1984 compete with the narcissism on display on a typical twentysomething’s social media account?

No, Foreign Affairs underscores my feeling that an era that could produce art like this, Mass Appeal, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and Amadeus couldn’t have been superficial—not at its core.

The quieter, slower-paced world of the book, in which there is the outside, public world, and the interior, private life, with the walls of the characters’ homes or apartments physically separating these two spaces, also represents, unintentionally, an entire vanished era. Only, it’s not vanished—not for me and, I suspect, not for many others who lived through it. It’s startling to contemplate all this now, because at the time the 1980s seemed so bright and frantic. But now they have become a sort of Walden in Generation X’s collective psyche. I understand that for me, the 1980s never ended—just as the 1960s never ended for so many in my parents’ generation. And as for the subsequent decades, why can’t they f*ing get in line? It’s not me who should adjust! I can’t adjust, not fully. It's the rest of the world that needs to cohere! To reconcile itself with what I thought life was, and what the future would hold. I will carry this delusion onward.

But, of course, the world has moved on. It will mine aspects of our decade when convenient. It will delight in our synth sounds. It will laugh at our hair and our bright colors and optimism. How quaint! And all of that, I understand, is necessary. Don’t I do that with the 1960s, with the barely remembered 1970s, with all previous eras I never lived through, but which offer up flashes of art and ephemera out of context?

Anyway, I will carry the delusion until I expire, and it’s fine. Maybe it’s not a delusion; maybe it’s survival. We hold onto the things that shaped us. We adapt as needed—but only so far. If you were blessed to grow up in a time when you felt happy and in-step with the zeitgeist, what possible motivation would there be to move on? (I realize this contradicts what I wrote last month about needing to move on. Somehow, both impulses are sincere and necessary).

But I can hear the scolding voice of the present: There are no black people in Foreign Affairs! It’s true, and historically correct—the 1980s’ world of English entertainers and American expatriate academics Lurie depicts would not have harbored a lot of racial diversity. If the book were written now, the author might feel compelled to have a person of color featured prominently in the cast of characters—and such a gesture might be appropriate. The world may not be ascending in quite the way that progressives would wish (the “long march”), but we have lurched in certain directions, past the embarrassing spectacle of, on the one side, guilt-stricken white people loudly atoning (often drowning out the people who have actual grievances), and on the other, the boorish counterreaction, to shakily land just a few steps ahead of where we were. Our neighborhoods and college campuses and workplaces of 2022 may be roiling with conflict and resentment. They are also, quite visibly, more diverse than they were four decades ago. It may be that all the shouting about people not having a place at the table is evidence that there are now more people at the table.

*****

Kuwait Airways Flight 221 hijacking. I remember whispers, frantic discussions among the grown-ups about this event, which unfolded at the Tehran airport in front of a seemingly indifferent Iranian government. In the long run, it was all so pointless—as terror attacks usually are.

The lens pulls back wider. 1984 was not so sunny for those passengers and their families. Nor for the victims of the Bhopal disaster, an industrial accident (the worst in history, according to Wikipedia) that occurred in India on Dec 2-3. Nor for the victims of the previous month’s San Juanico disaster, a catastrophic combination of fires and explosions at a liquefied petroleum gas storage facility in Mexico.

On the clearest and most joyous days for some, there is agony for others—sometimes due to accident, sometimes due to malicious intent, the scale of suffering often compounded by the scale of our technological ingenuity. That is a difficult realization to live with.

December 22, 1984 / August 22, 2022

“Careless Whisper” arrives. This song was everywhere. I remember that greasy sax line blaring from the open door of the school bus at dismissal time. Its iconic status lies in the future, though. For the moment it’s just another song quietly entering the Top 40.

The time tunnel is closing. The time tunnel never closed. What’s left of the 1984 gang in congregating around Sirius XM’s “80s on 8” channel. Former MTV VJ Nina Blackwood is raspy but on her game. Mark Goodman, who strikes me in 1984 as cocky with a bit of a cruel streak (an offhand crack I hear him make about Boy George in ’84 would likely get him canceled in 2022) has been sanded down by Time the Conqueror into a lovely human being. I recently (in 2022) heard him introduce Mike and the Mechanics’ “The Living Years”—a song about father-son relationships that gains force only as the listener grows older—on Sirius XM, and he said, quite sincerely, “I’m going to need to leave the room when this starts playing.”

Rick Springfield bounces between “80s on 8” and the Beatles channel. A confluence of factors—age, a lifelong battle with depression, and the fading away of fame and recognizability, have enabled his best qualities to become more prominent. Anyone who heard his minor hit “Bruce” (which charted in 1984, though it was recorded earlier) would have already known that he’s funny, but few could have anticipated the depth of his surrealistic loopiness, his impeccable comic timing, the jockeying of real wisdom with calculated satire, all of which he brings to his DJ gig on Sirius XM. I haven’t spent enough time with his music to assess it, but Rick Springfield the man is a treasure.

Time often does good work to those who hold on. We ought to use the term “has-been” sparingly, if at all. The celebrity spotlight is finite and often arbitrary. Those lives not incinerated by it continue on after their “15 minutes of fame” have elapsed. And I suspect that the 16th minute is more interesting and meaningful than what came before.

December 29, 1984 / September 5, 2022

It was a good year for: Huey Lewis, Phil Collis, Hall and Oates, Michael Jackson, Boy George & Culture Club. It was a spectacular year for Lionel Richie: People forget that the world was his to lose in the mid-1980s, that he was compared favorably to Paul McCartney, that in the Summer Olympics closing ceremony broadcast he performed for more people—a couple billion viewers—than any other music artist had ever done. 1984 was also spectacular for Prince, for Madonna, and especially for Cyndi Lauper, who was similarly poised to take over the world. It’s tempting to think that Cyndi didn’t deliver on her promise, but I’d like to think she pulled back to a level she could sustain.

At the close of 1984, Gorbachev makes his first major trip west. He is not the leader of the Soviet Union yet, but he is the heir apparent and we want him in power. There is already the sense that this is a man we can do business with. In 2022 Gorbachev dies, and as I sit at the beginning and ending of his world-changing arc, I wonder what he ultimately thought about it all. Did he move the world forward or backward? We’re grateful to him, to be sure, but I wonder if we wouldn’t rather deal with his era’s Russia than Putin’s?

December 31. 1984 / September 17, 2022

David Lean’s stridently out-of-step A Passage to India accidentally manages to be in-step due to current (1984) events in India: Sikh insurrections, the assassination of Indira Gandhi, the Bhopal tragedy—all of which mirror the movie’s examination of the fallout that can occur when we attempt to bridge irreconcilable cultural chasms. What is the meaning in all this? How is it that people cannot communicate with one another? What recourse is there but to retreat, a la Alec Guiness’s character Professor Godbole, into detachment and contemplation? (But if we do so, does our contemplation reveal the casting of the very English Guiness in the role of an Indian mystic to be an example of the tone-deafness the movie is critiquing?)

Whatever its own blind spots, A Passage to India is a fine movie. In 1984 we have encountered, from the Reagan administration and also from popular media such as “God Bless the USA” and Missing in Action, moral certainty. As a child, I found this comforting. My country was good and my community was good. We were all moving forward, on the right side of history.

But as an adult, I’m happy to discover there was a 1984 for grown-ups, and Foreign Affairs and A Passage to India were part of that. A common theme in these works is that it is impossible to know another human being’s heart, and that the things we think we know about other people, and by extension, those moral certainties, are either wrong or incomplete. Does this negate my ten-year-old self’s perception of 1984? No. Both are accurate representations of the time and place, but in my grown-up perception, the lens has been expanded. If I were to come back to 1984 again in forty more years’ time (Good Lord, at 88?), the lens would be wider still.

*****

Quick thoughts on MTV’s New Year’s Ball: Seeing this in the harsh light of video (as opposed to so much of the listening I’ve been doing) in a way diminishes what I’ve just been living through. Here are the tawdry, bright, cheap, and (apparently) jacked-to-the-gills-on-cocaine-and-God-knows-what-else 1980s I’ve been hearing about. And the commercials—also jacked up! Just shy of panic-inducing! (Although it is great to see the Fat Boys in a Swatch commercial.) What a shock after the stately A Passage to India and the contemplative Foreign Affairs. And yet—there is a wildness and playfulness to this early MTV that seems wholly absent today. Martha Quinn is kind of an early “type” for me that lodged in my psyche and didn’t let go. David Lee Roth may be juvenile bordering on toxic, but I enjoy his surrealism, and that he seems to regard the entire spectacle—rock ‘n’ roll, stardom, possibly life itself—as a cosmic joke. If we were to tie this all together, maybe there is just a little bit—I mean a teensy weensy trace element—of Passage to India’s Professor Godbole in Roth. No? Did I lose you?

I feel a stab of loss as the end-of-year countdown begins. 1984 is over again. While I was living it, there was the feeling that it continued on and could be stretched out like taffy (which I have done to the fullest extent). But now the door closes. I will be processing all this for quite some time. In keeping with the idea, from Fitzgerald, of the salutary benefits of maintaining two opposing ideas in one’s head at the same time, I am both exhilarated and melancholy.

And, just as I would feel after midnight on January 1, 1985, I am exhausted.

I am going to sleep.