Listening to 1984: An Experiment in Time Travel - Part 9 of 12

It’s September and the gang’s all here: Wolfe & Mailer, Karen Allen, Metallica, Don Johnson, John Barry, and the Huxtables. Plus, you don’t have to watch “Dynasty” to have an attitude, but it helps!

The story so far: Sometime in 2019, I had a premonition that 2020 was going to suck. So— I decided to spend the year re-experiencing my favorite year from my childhood: 1984. By "re-experiencing" I mean listening to the music, watching the TV shows and movies, reading the news magazines and books, and listening to "American Top 40" and "Newsweek on Air" week-in, week-out, in chronological order. Weirdness ensued. I kept a journal. It took longer than expected, and by spring 2021 I was still in 1984…

(Note: If you just came onboard and are thoroughly confused, start with Part 1.)

September 14, 1984 / May 21, 2021

The Bonfire of the Vanities! Serialized in Rolling Stone! Tom Wolfe – a very loud writer! Likes exclamation points! Well, he’s no Bill Gibson, let me tell you; but Vanities says something about the ‘80s—it is as of its time as Neuromancer is beyond it: all brightness and perfumed and pastelled; full of status-hungry characters jockeying for recognition and power. Here is the shallowness I’ve been hearing about, Wolfe attempting to pin it down and become the decade’s Dickens. Question: Is he channeling something or inventing something that future commentators would run with, thinking he had captured the thing when he had, in fact, only captured a thing?

While there may have been a media monoculture in the ‘80s, regional cultures—like the frantic New York City high society Wolfe describes here—were still distinct. Not much of the Bonfires world filtered down to Minneapolis. I remember when the book version landed a few years later; my secondhand impression, based on the reactions of the adults who were reading it, was that it depicted an exotic, shimmering, foreign world—not much to do with the Great Lakes, the IDS Tower, and the Minneapolis Athletic Club (although a novel depicting cutthroat power-plays in the upper echelons of the Twin Cities’ moneyed class would be something to see).

But Wolfe—all these years I’ve been thinking of him as a kindred spirit: the offbeat conservative mixing it up with outrageous counterculture types, filing his report, getting it all down. But I’m on the fence about his style. Like his compatriot Hunter S. Thompson (and like their apparent film analog, Nigel from This is Spinal Tap), his volume seems stuck at 11. My friend Kyle King, who I generally trust in these matters, insists that Wolfe’s fiction and nonfiction are two different beasts. Surely The Right Stuff isn’t written like this. But right now I’ve got to play with the cards I’m dealt, so it’s onward with this hot-take, excitable, serialized version of Bonfire of the Vanities!!

September 14, 1984 / June 2, 2021

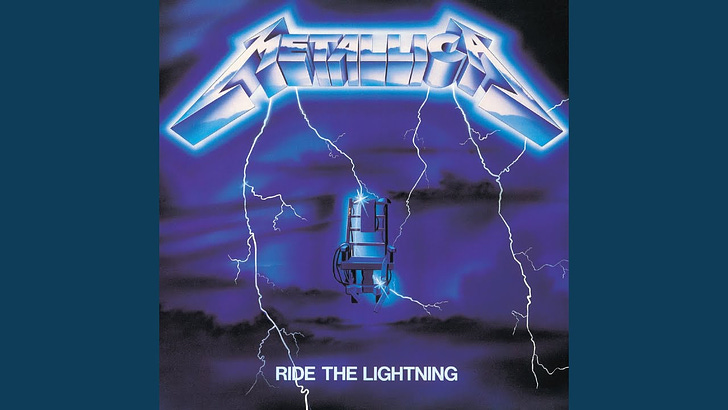

Wonder of wonders, Metallica’s Ride the Lightning is a masterpiece. This is something that would not have been on my radar were it not for this project, but I recognize a near-perfect album when I hear one. And it follows Jimmy Page’s “light and shade” template: There are baroque interludes of quietly plucked acoustic guitars, drums and bass trotting along like a Shetland pony. Never for long—this is a Metallica album—but long enough to allow me to breathe. And I gotta say, when the trademark Metallica crunch kicks in, it’s never unwelcome. I see more clearly there are not many miles between the classically inflected passages and the metal—at least the way these guys do it. The guitars are heavily distorted, but this is not a wall of smeared noise like you’d get from Sonic Youth or the Stooges (much as I enjoy that). Everything here is tightly controlled, stopping and starting on a dime. There are no wasted notes, no errant guitar squalls anywhere on the album. My only complaint is James Hetfield’s over-reliance on double-tracked vocals—the only element that signals any sort of lack of confidence. Otherwise, Ride the Lightning is a formidable statement of intent. It rocks, and it doesn’t sound like it came from 1984 or any other specific year.

September 15, 1984 / June 9, 2021

Norman Mailer, I guess I’m not supposed to love you but I can’t help myself. In 2021 you would never get your career off the ground, but in 1984 you’re still hanging in there, getting the good interviews, the well-placed reviews, still considered one of the “it” boys of American literature. This despite the very mixed response to your 1983 novel Ancient Evenings; your excoriation by the feminist movement in the 1970s; your myriad linguistic and personal excesses—you are arguably the most politically incorrect major author of the modern era; and, oh yeah, you stabbed your wife a couple decades back: an event that no one will stop mentioning because, well, you stabbed your wife. Astonishingly, you’ve been celebrated as a key voice of the political left for much of your career. (Dorothy, we’re not in 2021 anymore.)

So we have here a thriller, Tough Guys Don’t Dance, which is essentially the plot of The Hangover 25 years early with a couple of decapitated heads thrown in, and it has all the expected Mailerian tics, all the “Did he really just write that?” moments. But it is also an impossible-to-put-down neo-noir page-turner. Not too many other “A-list” literary types can do this for me. (I remember two long passages from Mailer’s later novel Harlot’s Ghost that pulled me in for hours; during those stretches, I could no more put that book down than a surfer could extricate himself from the middle of a pipe. And we’re talking long passages: 20-40 page runs.) What can be the secret sauce? Something in the demented exuberance of the writing itself, or the author’s commitment to full-bore living? Can we separate the two?

Between the covers, the outrageousness is a feature, not a bug. In its flamboyant darkness, Tough Guys is the literary equivalent of Metallica’s Ride the Lightning: everything at 11 (Mailer, like Wolfe, is a fan of exclamation marks), executed with confidence and technical mastery. And if we are to continue with this hard rock analogy, we could also say that Tom Wolfe, in contrast to Mailer’s dark metal, is Van Halen: all brightness and panache. (Hell, he wears the spats.) It’s fun to see these old ‘60s iconoclasts resurfacing and going head-to-head in the ‘80s.

Now, the content of this book—oh God, not for the faint of heart! Hapless protagonist Tim Madden—a tenuously employed sometime-bartender and frustrated writer—unwittingly leaves a trail of mayhem in his wake as he attempts to figure out what happened during an alcoholic blackout that left him with a new tattoo, a car seat soaked with blood, and two human heads crammed in the hidey-hole for his marijuana stash. Most of Mailer’s novels are written in first person (although, unusually, he often wrote about himself in third person—as “Mailer”—in his nonfiction) and the narrator is always some variation of Norman, or of Norman’s public persona. Which means we get an over-amped (very un-#Me Too, if we’re carrying our contemporary baggage) sexuality, a simmering rage, an oversized ego, and a compulsive need to push just beyond the boundaries of taste and propriety—perhaps not quite so far as Henry Miller and William Burroughs, but firmly over the fence. And I can’t stay away, even after the jarringly racist passage he laid on me last night about blonde women and black men. It’s all part of the whole: by turns infuriating, exhilarating, repellent, always alive. I have never seen a narrative jump out of its track so often, only to lock back in so hard, so intensely as to give the reader a visceral rush. It’s the feeling of the bat connecting squarely with the pitch after three balls, two strikes, at the bottom of the ninth, the power of the hit traveling up the arms, through the shoulders, into the chest—that loud snap! echoing through the ballpark, the ball itself sailing just out of reach of the center fielder’s glove. This happens over and over again in Tough Guys Don’t Dace. There are many bottom-of-the-ninths here! And I’ll take all the bad with the good just to experience that alchemy of faded print leaping off dead tress to dance before my eyes in a hard won, skin-of-the teeth victory.

(2024 Editor’s note: Readers would be well-advised to steer clear of the Mailer-directed 1987 film adaptation of Tough Guys Don’t Dance, which earned Mailer a Golden Raspberry for Worst Director, an honor he shared in a tie with Ishtar’s Elaine May. The film enjoyed several other Golden Raspberry nominations, including Worst Picture and Worst Screenplay).

September 16, 1984 / June 18, 2021

Miami Vice ticks all the boxes of police-show formula: brooding undercover cop with a flashy exterior and troubled home life; a beloved partner unceremoniously dispatched in the opening scene to add further pathos while making way for the arrival of the co-star; a revenge arc (“He killed my brother!”); trigger-happy drug dealers. The plot is often rote and the acting is all over the place, but the original Miami Vice jumps off the screen even now. The music; the color; Don Johnson’s meticulously landscaped stubble and trademark uniform of baggy white pants, light sportscoat, and pastel-hued, torso-hugging T-shirt; the cinematography; and the location—which is the real star of the show; all of these qualities combine to make this a groundbreaking moment in pop culture.

For some reason, Miami Vice was not popular in the Lurie home. I’m not sure why; my dad enjoyed Hawaii Five-0 and Magnum, P.I. and seemed to have an appetite for these sorts of exotic mystery shows. I suspect my parents thought it was too violent, too risqué, too “MTV.”

But anyway, I ought to mention Don Johnson’s hair since I spent so much time on Reagan, Mondale, and Ballesteros’s coifs in previous installments. In this year of signature haircuts, his is perhaps the most impressive: not big, not ostentatious, just silky, vibrant, perfectly swept back yet apt to fall into his eyes or lift up in the breeze. We can only wonder how much work went into that hair, that tan, those white teeth, and that stubble. And yet, while he is handsome—a prototype of what will briefly be termed metrosexual—he’s not exactly a pretty boy. He talks in a raspy voice that sounds ten years older than its container, chain smokes, and has a weariness in his eyes that signals just how long it took to get here. At 34 he’s a veritable senior citizen in Hollywood and has languished for years in ill-fated projects, yet he comes roaring through this pilot as if he has a string of blockbuster films behind him. And Philip Michael Thomas as Tubbs, well, he’s rough around the edges, but it takes some talent to sell the scene where he mimes Maxwell’s “Somebody’s Watching Me” to a stripper.

Miami Vice may be the defining TV show of the 1980s. It is, above all, about style. It is bright, loud, vibrantly alive. There is some substance—the scene where Crockett confronts the “mole,” who turns out to be his partner, is genuinely affecting—but even during its predictable stretches, it is artfully put together. Hill Street Blues is a more substantive show that transcends its era, but it is an outlier. Miami Vice owns its glorious time, and it is instantly one of my favorite shows.

September 19, 1984 / June 30, 2021

Amadeus: Here is proof that timeless art could emerge in the midst of a very time-stamped era. It’s not as much of a throwback as John Huston’s contemporaneous Under the Volcano, but it has a classic feel nonetheless. And yet, when I originally watched this—or tried to watch it—on pay per view or video shortly after its release, I didn’t understand it. Like the uncomprehending Viennese, I was deaf to the charms of Mozart. I was put off by Wolfgang’s vulgarity, his seeming superficiality, his effeteness, and his ridiculous giggle.

I was eleven, or possibly twelve, when I became aware of this movie—my dreams just beginning to crystallize. What could I know of Salieri’s torment: blessed with the ability to see and hear greatness, to recognize God’s voice on earth in the music of Mozart, but cursed by a lack of talent, or, rather, talent that only went so far. Outwardly, a figure of achievement: the court composer, lauded by his monarch and his countrymen. Inwardly, a man torn apart by a dream denied. Salieri is driven to the darkest of places by his inability to be at peace with himself. What could I have known of such things? Fifth grade was difficult. Sixth grade was difficult. But these were a child’s difficulties—bewilderment at the changing social dynamic as my classmates and I lurched toward puberty. Existential questions of worth, of the heart’s striving, of what one can reasonably expect from God and from life—these were rightly out of the reach of children’s concerns, or at least were then.

What a blessing to see and appreciate this movie now, even if it does light up a bit of my inner Salieri.

“Mediocrities of the world, I absolve you all”: These are the last words of the film, declaimed by Salieri as he is wheeled through the asylum where he will spend his final days. The irony is that Salieri—as played by F. Murray Abraham and as envisaged by director Milos Forman and screenwriter Peter Shaffer; scheming, tormented, brooding Salieri—is anything but a mediocrity. And the movie is the antithesis of mediocrity. It’s a wonderful film, but there is something deeply flawed in its worldview—or, if not flawed, something I should ignore: a conception in which there are only a few divinely touched geniuses amongst a swelling horde of artistic mediocrities who can never hope to advance to greatness. That there is an overwhelming amount of bad or unengaging art in the world cannot be disputed; there are plenty of modern day Salieris: “court composers” of some ability who have simply reached their ceiling. But the fixed geniuses-vs-mediocrities model ignores the fact that most artists start out “bad,” fumble their way upwards, and then, if they are lucky enough to attain a level of mastery—what we might call “genius”—it often ebbs and flows over the course of the succeeding career. A “genius” can be capable of much mediocrity. And a seemingly mediocre talent can punch through that malleable ceiling to something greater. It’s all a moving target and God is restless in his aim. (I suspect that if the Salieri of this movie had managed to bottle all of his impotent fury into a piece of music rather than a convoluted revenge plot, it could have resulted in transcendent art).

There is a danger that fledgling artists could see Amadeus at the wrong point in their formation and think, “Why bother? I wasn’t playing sonatas blindfolded for the Pope at age seven; maybe I need to look into something else to do with my life.”

So yes, anyone with the faintest of creative strivings would be well advised to ignore the message of this movie. At the same time, I would be suspicious of any aspiring creative who was not enthralled by every other aspect of it.

September 19, 1984 / July 2, 2021

The Afternoon the Earth Stood Still…

WCCO 5 PM News: Across the city, across the state, across the country, there is little going on this afternoon in 1984. I can’t comprehend this in 2021—an eerie stillness. Yes, there are, as ever, wolves at the door: a couple of new indictments in an ongoing abuse investigation at the Children’s Theater; a man discovered with a knife at a Mondale Rally in San Francisco; and further speculation about the Chicago Tylenol killings of a few years back. But in terms of immediate events… well, the jury is out for an important sex abuse trial but they’re not going to decide anything anytime soon; in fact, the jurors all went to a restaurant down the street. Meanwhile, the state Republican Party has asked Reagan to make a visit to Minnesota sometime during his campaign; someone at the White House is going to present this idea to him sometime soon. An onerous alcohol tax that had been paying off construction of the Metrodome stadium has been repealed. And the North Stars (hockey team) have hired physical therapists to help fine-tune their exercise regimen. Things perk up a little with the day’s weather report: 91 degrees Fahrenheit with 30 degrees humidity; unusual for September—the last Sep 19 to hit these levels was in 1897.

Sweet, lost era. No one has figured out yet that you can do a split-screen with two or more heads yelling at each other. There is no social media to mine for the latest outrage. The provocative content—the child abuse material—is covered tactfully. Beyond that, there is simply little news today. People went to work and lived their lives. Bad things surely happened, but they were mostly private or far-off tragedies that did not make it onto the early evening screen. So, a requiem for one afternoon of rest: September 19, 1984. Will we ever see its like again?

September 20, 1984 / July 2, 2021

The Cosby Show premieres. A lot of critical ink has been spilled over this show—a lot of well-intentioned debate over its racial, cultural, political ramifications. I’ll leave the pundits to it. I can only speak to the show’s impact on me, my family, and my 10-year-old peers in 1984. I know that Between the World and Me sold a lot of copies and that Ta-Nehisi Coates is a brilliant man. I know that Selma and Moonlight are well-regarded movies that made an impact. But Cosby was everywhere, and it sparked conversations on race in places that those other books and films will never penetrate. Maybe it did so by sugarcoating, by being unthreatening; again, that is for other people to parse. But it was unstoppable. Everyone watched it. As my friend Matt Brown pointed out to me recently, it went head-to-head with Magnum P.I. in its timeslot and dethroned that heretofore ironclad juggernaut. And to my modern sensibilities it still seems quietly revolutionary: an upwardly mobile black family—the father a doctor, the mother a lawyer, the children college-bound—simply go about their lives. They were confident and unapologetically African American. You’d better believe that these families existed, but they hadn’t often been depicted onscreen before. By and large, the majority of black roles still fit the mold of Moses (the character played by Danny Glover in the Oscar-bait film Places of the Heart, which premiered one day after Cosby): intelligent, dignified, but also poor, oppressed, needing the helping hand of Sally Field or some other benevolent white character, speaking the words and acting the stories dispensed by compassionate white writers—in the case of Places, Robert Benton. This type of storyline has a history going back at least to To Kill a Mockingbird. Cosby in 1984 is new territory.

Of course, there is a whole new layer of complication to this narrative: the figure of Bill Cosby himself. But I’ll try to imagine for a moment that I’m watching this as an adult in 1984, with no knowledge of what is to come.

I think I would still detect an edge. Cosby broods, he scowls. Nine out of ten times he breaks toward warmth but there lurks an impression that he could explode in rage. This is all played light—yoked to the comedic beats. But it also feels intrinsic to him. I don’t see this in comedians often—maybe in James Belushi and very occasionally in Chris Farley.

Am I reading the present into the past despite my best efforts? Did Bill Cosby really wear his demons so close to the surface, or are the two things not tied together at all? I’ll never know. But I do know that The Cosby Show stands independent of all this—that it succeeds and endures in spite of the overwhelming baggage now attached to its lead actor and co-creator. And all of this is abundantly clear in a pilot episode that doesn’t contain even a shred of a plot. It’s all about the characters, the performances, the declaration of intent. In these waning months of the year, The Cosby Show rules 1984.

September 21, 1984 / August 9, 2021

Just a few seconds into the opening theme of Until September and the hairs on my arm stand up: John Barry! Composer of the iconic early Bond scores and, later, Born Free, Out of Africa, and Dances with Wolves… I hadn’t expected him here.

The main chord progression begins with a C chord, but the subsequent switch from C to F# is trademark Barry: a subtle shift from stability to uncertainty. The following A-minor only heightens that feeling, then, with D-minor to G to C, we’re back on secure footing. He’s got us. But those moments of tension elevate Barry: The right contribution from him can turn the most ordinary film into something transcendent.

For me personally, there is a feeling of completion, of just-rightness, as my favorite composer shows up on the scene unexpectedly. The gang is truly all here in 1984.

Of the film itself (which was not a commercial success) well, it’s not great. But I enjoyed it more than a little. It has Barry’s contribution, of course, but it also has Karen Allen. Yes, Marion Ravenwood from Raiders of the Lost Ark: “I’m your goddamn partner!” That Karen Allen. And I’ll wager there were very few ten-year-old boys in the 1980s who were not in some way in love with her. Here, as a stranded American tourist in France who falls in love with a married man, she is sweet, earthy, goofy, sincere. She’s unlike any major actress before or since: not a conventional beauty, but her wide, expressive eyes and smile own the screen. Add the husky voice and disarming laugh and she is alive, real, inhabiting her characters immediately and fully.

But the movie… it’s well-crafted, but I found male lead Thierry Lhermitte—or at least his character—to be thoroughly unlikable. Physically handsome, with eyes as striking as Karen’s, he plays an emotionally detached married man, a father (though the childcare arrangements are a bit confusing), and a keeper of several mistresses. Karen is too good for him, and we’re supposed to believe that his emotional breakthrough and declaration of love at the end will lead to happily ever after, etc. I’m sorry, but a lifetime of compartmentalization is going to set them up for failure. She’d fare better with Indiana Jones—at least he’s consistent.

The movie is predictable: It follows the established tropes of a “chick flick”: chance meeting, shaky courtship, “will they or won’t they” tension, passionate consummation, complications, reconciliation. But it’s Karen Allen in a rare starring role. For whatever reason, there weren’t too many of these and I’ll take what I can get. Plus, it’s got Paris and John Barry. Does the movie transcend its limitations? No. But I’m happy I got to experience it.

September 26, 1984 / July 23, 2021

“You don’t have to watch Dynasty to have an attitude,” Prince will sing in 1986’s “Kiss” – such an odd line, in that it implies a pushback: that somewhere, someone did make the argument that having an attitude was contingent on watching Dynasty. But that’s the Princeverse for you: Like the Mailerverse of Tough Guys Don’t Dance, it follows an internal logic that is entirely consistent within the ‘verse but bears only a passing resemblance to reality. Starfish and coffee, anyone?

But I’m jumping ahead on the time-track. Dynasty has its season premiere tonight, and so I now come in contact with these figures that I have previously known via tabloid headlines and hushed conversations between my parents. We have Joan Collins—the conniving, insatiable “older woman” of the piece—except that I have to laugh because she’s roughly the age I am right now, and she looks youthful to me, definitely holding up well in spite of those cigarettes she’s smoking. Then there is Heather Locklear, who I take to be Collins’ scheming “younger woman” doppelganger. Except she is so young, bright eyed, sweet looking—can she really be a femme fatale? As with the boyish Charlie Sheen in Red Dawn, it is startling to see her so seemingly pure. Don’t get me wrong: Locklear plays the duplicitous siren with aplomb. But she also looks like what she is: a young woman barely out of her teens, and that proximity to innocence is, itself, a form of innocence.

Now, what does Dynasty tell us about the 1980s? It leans hard into the narrative that the decade was wealth obsessed. Hand-in-hand is the perception that the wealthy are constantly double-crossing each other and jockeying to either establish or maintain their positions of power. In Dynasty as well as its competing prime-time soap operas Dallas and Falcon Crest, murder is a readily available option in this struggle, and we’re led to believe that these conflicts—which sometimes appear to have the body count of a small country’s civil war—play out routinely in the wine, oil, and cattle industries.

But I will get off my high horse because the show is instantly addictive. It’s great fun to watch and it looks like it was fun to make.

September 29, 1984 / August 13, 2021

“Torture” by the Jacksons: a great little song that thoroughly redeems them after the atrocity of “State of Shock.” Now here is a mystery: The Jacksons’ Victory was a commercially successful album, and the “Victory” tour, despite a number of business and production snafus, was huge: It was the de facto tour for Thriller, since Michael never toured that album solo. As I learned from Casey Kasem yesterday, just the crew for this trek numbered in the thousands. So my question: Why has the entire thing vanished from history? This was not a case of intended cultural cancellation a la Bill Cosby; this was a cultural Bermuda Triangle that swallowed up the biggest act of the year. By the end of the decade, when people thought about Michael Jackson, they thought: Thriller, moonwalk, maybe the Pepsi commercial when his hair caught on fire (but forgetting his brothers were in that commercial too), Bad, maybe even Captain Eo, but—no Jacksons, no Victory tour. Gone. Not even an indentation in the time-space continuum. And Jermaine Jackson: he was big, he was charting, he was on his way. What happened?

Well, as we near the end of September 1984, the tour is underway. The songs are climbing up the chart, life is good—albeit fraught with the usual Jackson family squabbles. (Michael refuses to appear in the “Torture” video and is replaced with a wax dummy). To all appearances, the Jacksons own 1984. Who could have known they were simply leasing it and would return it on January 1, 1985 untouched, in the same condition in which they found it. That is a different sort of Faustian bargain than I’ve ever heard of.

September 30, 1984 / August 19, 2021

Snapshots: Administration officials scramble in the messy aftermath of another Beirut bombing. Reagan has his first meeting with Gromyko after 3 ½ years of a Big Diplomatic Chill. The candidates prepare for their upcoming debates. Meanwhile, Iacocca’s memoir flies off the shelves. The fall TV season is underway. Movie theaters swap out the crowd-pleasers for the Oscar-chasers. Things are happening—albeit not obviously connected things. I’m thinking of the conversation I had last night (in 2021) with my friend, author/journalist John J. Miller: “What is your elevator pitch for 1984, and for this project?” he asked. Perhaps my pitch is that there is no elevator pitch; that, in fact, the tendency to distill our unruly history into elevator pitches and capsule summaries is precisely what brought me back here for a second look. Real life flees from these ideas of “Year X was when the future began.” 1984 is indeed a year of consequence: socially, culturally, politically; but it is also a big messy surge of energy.

We do 1984 an injustice to boil it down to bullet points, but perhaps the year does function as an effective avatar—if that is the right word—for the entirety of the 1980s, for surely all of the qualities that distinguish the decade are represented here: the style, the sound, the energy, the optimism, as well as the shadow side of geopolitical uncertainty and a virus (AIDS) that most people would like to ignore but can’t. In the face of all this, the myth that immediately evaporates is the one about the 1980s being materialistic and superficial to the exclusion of much else. Certainly those qualities are present in what I’m seeing, reading, and hearing, but they compete with a myriad of other sharply opposed impulses.

In “living” this year again, I have re-experienced it as something closer to what it may have actually been: twelve months of people moving through their lives against a backdrop of the momentous and the mundane. Perhaps that is my elevator pitch.

Next up: Part 10