Listening to 1984: An Experiment in Time Travel - Part 6 of 12

"Star Trek III" resurrects the 20th century male—in the 23rd century; breakdancing sweeps the nation; Bill Murray anti-acts; and Ernie Hudson suffers the indignities of "Ghostbusting while black."

The story so far: Sometime in 2019, I had a premonition that 2020 was going to suck. So— I decided to spend the year re-experiencing my favorite year from my childhood: 1984. By "re-experiencing" I mean listening to the music, watching the TV shows and movies, reading the news magazines and books, and listening to "American Top 40" and "Newsweek on Air" week-in, week-out, in chronological order. Weirdness ensued. I kept a journal.

(Note: If you just came onboard and are thoroughly confused, start with Part 1.)

June 10, 1984 / June 10, 2020

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock. I have given too much of my life to this movie. Sometime in late 1984 or early 1985, I videotaped it off pay-per-view. Over the next couple of years, I wore the tape down. Does Star Trek III deserve all that attention? Probably not when viewed through the prism of Vulcan logic. But it’s the one that came on when I had the VCR queued up.

So, what do we have to look forward to in the 23rd century? Despite Star Trek II director/screenwriter Nicholas Meyer’s comment that the Star Trek future appears to be populated by (I’m paraphrasing from memory) politically correct golfers, unreconstructed males are back in the form of Jim Kirk, Khan Noonien Singh (Kirk’s adversary in the previous film—who at least had the excuse of being a cryogenically frozen holdover from the 20th century), and this latest installment’s delightfully aggressive Klingon Commander Kruge. I guess some aspects of human—and alien—nature just can’t be scrubbed out.

We (okay, I) have also learned from the Star Trek III novelization that both humans and aliens have mastered the art of “controlling biometrics” during intercourse, thereby avoiding pregnancy. (Jim Kirk apparently failed at this technique, resulting in an annoying son who must now be killed off if the franchise is to continue).

A new Cold War has come about, spurred by a startling technological advancement: the “Genesis Device.” The scientists who developed Genesis are stunningly naïve about the destructive implications of their creation, which, in its ability to create fertile new planets will obliterate whatever might have resided there previously; destructive implications, I should add, that both Starfleet and its adversaries picked up on immediately.

In short, apart from the birth control breakthrough, not much has changed in 200 years, though the 23rd century, even with its marauding Klingons, genetically engineered maniacs, and world-destroying technology, seems more stable than 2020, so I’ll take it. Also, earth tones and flip-phones are back.

The most quoted line from the 1980s Star Trek series is “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few—or the one,” a beautiful sentiment that propelled Spock toward self-sacrifice in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. But I get some satisfaction from Kirk’s cheeky rejoinder at the close of Star Trek III: “The needs of the one outweigh the needs of the many”—a decisive repudiation of the social contract from the 23rd century’s most independent spirit. Libertarianism wins!

Now, some thoughts on the distorting lens of nostalgia: The 1980s Star Trek movies are well-made, entertaining films—fine examples of what summer blockbusters can be. But for newer viewers there is no way they can carry the power and weight that they did for those of us who saw them when they came out. The Star Trek movies work for my generation, and for my parents’ generation, because of an accumulation of goodwill toward the characters and the actors that played them. The original Star Trek universe was a shared reverie. My parents experienced the adventures of the starship Enterprise in real time, in 1966-1969. My generation experienced those same adventures every weekday afternoon in syndication. The further adventures most effectively depicted in II, III, IV, and VI carried the weight of that history. I understand that William Shatner’s acting is considered “hammy.” But to us, the Enterprise’s fellow travelers, William Shatner is merely the human vessel—the rental car—for the entity that is Kirk. Shatner can play T.J. Hooker or host Rescue 911 or become the spokesman for Priceline.com; it has no bearing on Kirk, as long as Kirk can beam in for the next Trek installment. Kirk isn’t hammy: He is playing to the rafters of his life. Similarly, Spock inhabits Nimoy, Bones inhabits Kelley, Uhura inhabits Nichols, not the other way around. That’s how I see it, and I suspect that’s how many Boomers and Gen Xers see it. And when things go off the rails, as they did in Star Trek V or perhaps the Generations mashup movie, well, there must have been static in the transmission.

The Enterprise occupies a similar place of reverence: That ship has been across the universe and back. So, Kirk’s initiation of the ship’s self-destruct mechanism at a pivotal moment in Star Trek III is, for some of us, akin to blowing up the Statue of Liberty. “My God, Bones, what have I done?” — That line carries some serious fuckin’ weight!

I am certain that a new viewer would be impressed by that scene—it is one of the highlights of the movie—but it wouldn’t turn their world upside down like it did ours.

The Search for Spock worked for me as a kid. There are a lot of big feelings in this one: grief (twice over, if you count the death of Kirk’s son in the final third of the film), regret, loyalty, hope, redemption, renewal. The literal resurrection of Spock resonated with my Catholicism, as did the emphasis on the soul, the idea of the Genesis device and the attendant theme that human beings have no business playing God.

As an adult, I see the holes. What happened to Carol Marcus, Kirk’s onetime love (introduced in Star Trek II) who seemed to be warming to him again? Why didn’t Kirk save his son by faux-surrendering and pulling his gangsta move with the Enterprise five minutes earlier? (Okay, I’m Monday-Morning quarterbacking with that one). One of the more powerful scenes—the Vulcan priestess telling Sarek (Spock’s father) that the prospect of returning Spock’s soul to his body is illogical, and Sarek responding, “My logic is uncertain where my son is concerned”—is undermined by an obvious question: How is it not logical? You’ve got a living but mentally vacant Spock on one side, and on the other, a split-personality Dr. McCoy being slowly driven insane by having Spock’s consciousness parked in his brain. In these circumstances, passing Spock’s “marbles” back to their owner would seem to be the only logical choice. Otherwise, what do you do with reborn Spock, put him in a Vulcan assisted-living facility? So yeah, it’s a little shaky. And I also recognize that the entire movie is essentially a salvage job born of two “oh shit” realizations that dawned on the Trek team at the completion of Star Trek II: 1) How do we continue this blockbuster series when we have just killed off its most popular character? And, 2) What to do with this annoying son we’ve saddled Kirk with? (The solutions: Bring #1 back to life and kill #2, brutally.)

Yet the fact remains that this movie, and its predecessor, taught me enduring lessons about friendship and sacrifice, lessons that resonated more deeply with me than scripture, despite the best efforts of my Catholic teachers. For better or worse, I have reflected on Spock’s “The needs of the many” line more often over the course of my life than anything out of the Bible.

June 8. 1984 / June 8, 2020

Breakdancing is sweeping the country in 1984—has been for the last few months, coinciding with the release of two movies: Breakin’ and Beat Street. I haven’t watched these yet, but the memories of the dance-offs are still vivid. Requirements: boombox, cassette of appropriate music (any of the up-tempo numbers from Thriller, especially “Beat It” and “PYT.”) And, most importantly, a large piece of cardboard to function as a mat. Broken-down refrigerator boxes are best.

Crank up the boombox at recess, put the cardboard down, form a circle. There were some surprisingly nimble breakers among the largely white Annunciation student body. I was not one, though I didn’t lack courage in jumping in and trying. I can feel it now—that adrenaline surge as I found myself out in the middle of the cardboard. What did I do? Feeble attempts at the moonwalk. And I remember trying to do the backspin. Excruciating moments, trying to help myself along with my hands, with no momentum and lots of body resistance. Real or imagined shouts of “Get him off the mat!” Then I’m out. And there is David Jaeger, or someone similarly dexterous, spinning madly like a top—just dropping down and spinning, then bouncing back up, wriggling like Gumby. No hands!

Breakin’—the beachhead of urban culture into white suburbia. Herbie Hancock’s “Rockit” is huge. Rap is ascending with Beat Street and some iconic albums about to explode into public consciousness. Yet even still, Michael Jackson rules the cosmos like all the Roman gods put together. Fast-forward to the future: There will be a movement in 2019 to posthumously “cancel” Michael due to new child abuse allegations. But Thriller cannot be removed from the landscape without creating an interdimensional sinkhole. Remove Thriller and everything else from the 60s-70s-80s get sucked down with it and the timestream is irrevocably altered, and suddenly we are walking around remembering John Denver’s chart-topping pop smashes from the tail-end of the second Carter administration, with Burt Reynolds continuing to rule the box office, basking in the success of Return of the Jedi (his third outing as the charmingly roguish Han Solo) and having just won the Oscar for his career-defining performance as Garrett Breedlove in Terms of Endearment.

No, Thriller must stay. So, in desperation, we cancel R. Kelly and the world remains standing. (I can’t erase “Down Low” or “Trapped in the Closet” from my personal memory banks though.)

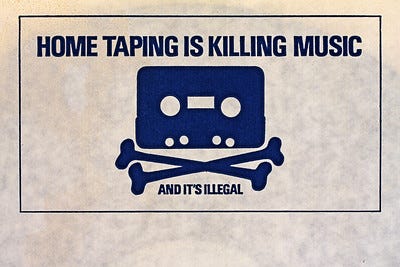

By the mid-‘80s we were carrying our music with us. The cassette was a liberating technology whose significance does not get the recognition it deserves. And the Sony Walkman was the first great “i” device, predating the iPod and iPhone by decades. But it wasn’t just the Walkman that made music’s new portability possible. Boomboxes were everywhere, and even if you didn’t have a portable player, you could just put a tape in your pocket and take it over to a friend’s house. The technology of dubbing came to the fore in the mid-’80s, and with it the concept of the mix tape (the one aspect of all this that has endured in the cultural memory).

Largely forgotten: the first great piracy scare: “Home taping is killing music!” Much ado about nothing—at least as the ‘80s unfolded. A music industry with Thriller in its midst could never be in ill health.

Of course, the limitation you run into with tape is the finite amount of music you can store on it. Unless you lug around your whole collection, you’re going to run out of stuff to listen to in about 90 minutes. This may be a good thing. It’s human scale. Anyway, that’s why most Walkmans (Walkmen?) had radios built in.

I still have some cassettes that I listen to and treasure, but I don’t miss the clutter that a big collection created. All those plastic cases so prone to breaking; those “J-cards” that we would pull out and pore over (they ought to have included magnifying glasses). And the ubiquitous peel-off Side-A and Side-B labels that came with blank tapes; I still have a lot of these spilling out of desk drawers—they multiplied ceaselessly, and yet they vanished when you actually needed them.

June 8, 1984 / June 8, 2020 – Part Two

Ghostbusters. Hilarious that in this movie that made Bill Murray a major star, Murray doesn’t seem to care at all about the script, his character, or acting itself—there is no pretense that his character actually could be a scientist. SNL was already in his past. Caddyshack had already happened. I know that the deadpan thing was his staple, but was there always this level of contempt in those previous—well, I don’t want to call them “efforts,” so should we go with outings? Robert Mitchum at least had physical presence to offset his “Baby, I don’t care” façade. But Murray works exclusively in acting antimatter. It is weirdly compelling. He makes you think that anyone could do what he does. But you don’t want anyone to do it but him.

Of course, this was all over my head at ten. I didn’t realize that Murray was supposed to be the cool one; that the other two guys were dweebs. I was into the uniforms, the gear, the headquarters, the car. So: another eye-opening bit of subtext I missed in childhood. It explains a few things.

But now I want to talk about the poster above, because it is time to right a historical injustice! As I have stated elsewhere, I am generally against coming down too hard on the past with the anvil of 2020 political correctness, but in the case of Ghostbusters, this is something I knew was wrong at the time. I’m talking about Ernie Hudson: Where is he on that poster??

Ernie was self-evidently a Ghostbuster, every bit the equal of Murray, Ackroyd, and Ramis. He had some of the best one-liners in the movie: “That’s a big twinkie”; “If there’s a steady paycheck in it, I’ll believe anything you say”; “Since I joined these men, I have seen shit that'll turn you white.” The second half of the movie has no play without him. So where is he on the poster? (And…insult upon insult, he wasn’t in the initial TV ad either.) There were four Ghostbusters, dammit, not three! And don’t give me the feeble argument that his character came in only after the “true” Ghostbusters were established and had some success. Ringo Starr didn’t join the Beatles until after they had built up a following at the Cavern Club and signed with Parlophone. He didn’t even play on their first single. But does anyone question Ringo’s status as a fully paid-up Beatle? No! No one who has breathed air since 1962—except perhaps Pete Best—has ever questioned Ringo’s legitimacy.

Yes, I’m being deliberately over-the-top. The screenplay and the actual movie do not give Hudson short shrift. But what was the deal with that ad campaign? Was Ernie paying the price for Ghostbusting while black?

Ah well. “Forget it, Jake. It’s 1984.”

(2024 Editor’s note: Turns out I wasn’t imagining any of this. Ernie Hudson opened up about the challenges of his Ghostbusters experience on Howard Stern last year):

June 8, 1984 / June 8, 2020 – Part Three

2020, why are you so insistent? Social distancing falls by the wayside as the country erupts in protests and riots over the death of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis police. There is an immediate and perplexing reaction from lawmakers. Last night my wife showed me a headline: “Minneapolis City Council Votes to Dismantle Police Department.” My rational brain understands that this could go either way; maybe the Minneapolis PD gets replaced with something better, fairer, more just. Maybe public safety is improved by this realignment.

But the lizard brain goes into overdrive, spurred by other announcements. Los Angeles Police Department has its budget cut by half. NYC government re-allocates some police funding. This in the midst of riots, anarchy, spiking homicide rates? I distrust the masses. The Black community, with justification, distrusts those in power. Hell, I distrust power too. And I distrust the media. And I distrust myself. 2020 has not been a good year. Not for anybody.

My 10-year-old self, on the other hand, knows little fear in 1984. My parents have done a good job of protecting me. But the adults are afraid—of drugs, crime, AIDS. Of nuclear Armageddon. Of the violence in faraway places—Beirut, El Salvador—somehow making its way home. Parents everywhere are always worried.

The #1 song in 1984 this week is “Let’s Hear It for the Boy” by Deniece Williams—a song that is, as my wife puts it, “frivolous.” But at this moment it’s the only thing I want to hear. I don’t want to hear the Cure, the Minutemen, Husker Du—not right now. I want to hear the Footloose soundtrack, Lionel Richie, Madonna. And Prince’s “Let’s Go Crazy” can’t come soon enough. (Although, that title…hmmm.) We’ve got Ghostbusters in the theaters. Yes, the culture is bright. But it seems to me that its lightness is hard-won, and I need it more in 2020 than I did in 1984.

June 9, 1984 / June 9, 2020

“Just remember, I don’t know who the good guys are yet.”

“Maybe there ain’t any,” Hawk said.

“Maybe there never will be,” I said, and got out of the Jag….

“You learning,” he said.-Robert B. Parker, Valediction

Robert B. Parker’s crime novel Valediction, published in 1984, offers layers of complexity that are sometimes in short supply in the Reagan era, but are right on point in 2020. The mindset is small-c conservative, by which I mean the old principle of “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.” Most of what Spenser (the P.I. protagonist) tries to do for the benefit of others blows up in his face, because the people he is trying to help are not, to a one, on the level. On the flipside, the book seems to make the argument that there is intrinsic value in trying anyway. I don’t get the impression that Robert B. Parker would ever make the wild argument that people have souls. But if he did, we could surmise that Spenser, in adhering to his code, is protecting his own.

A note on a minor plot point that ties Valediction to its era: Spenser dismisses Return of the Jedi, which he endures on a date night, saying that “it took about two hours” to sit through. But, he muses, “horses would have saved it.” Which strikes me as one of the book’s few optimistic notes: Some things might be salvageable. With horses.

A fine crime novel and a worthy kick-off, for me, to the literary side of 1984.

June 17, 1984 / June 17, 2020

Will I ever find a pleasure in my life to equal the feeling of waking up on a lazy summer morning in south Minneapolis? The air thick but still carrying the night’s coolness. We always had the windows open—with the screens on of course—because we had no air conditioning. So in the morning, I’d emerge gradually from sleep to the sounds of the neighborhood coming to life: cars starting, dogs barking, the clink of plates and rush of faucets. Sprinklers coming on. At some point, if I dallied too long, my mom would emerge at the side of the bed, chanting: “It’s time to get up, it’s time to get up, it’s time to get up in the morning!” Another line (I don’t know if it was the same song): “And this is the wayyy to start out the day / We’re all in our places with bright shining faces.” Did this happen every day of my childhood, or did it just feel like it?

Well, it didn’t happen on Christmas. We flipped the script there.

Summertime in Minneapolis can be brutal. The thickness of the humidity and the intensity of the mosquitoes cannot be exaggerated. But I’m having a hard time digging up any feelings other than happiness—and a longing to get back. I mean, all the way back. Back there and back then.

June 22, 1984 / June 22, 2020

The Karate Kid is the relieved exhale. Yes, 1984 is what I thought it was. It’s a lot of other things besides. But there is a moral center here that I recognize. Last month, Sixteen Candles depicted Asians as clowns. Then Gremlins traded on the stereotype of Asians as the exotic other. But in Pat Morita’s Mr. Miyagi, we have a dignified and authentic hero—by turns stoic and whimsical; complex, real. If there are flaws in the movie—if some of the other characters, such as the villains, are laughably two-dimensional, it is still propelled along by its enormous heart.

Karate – open hand … Force as a last resort … Wax on, wax off … Form a picture in your mind; if it comes from within you, it is perfect …

As I get deeper into the movie, I can’t shake the warm glow. It turns out that The Karate Kid had an outsize influence on my life that I hadn’t realized. Pat Morita fixing the Cobra Kai teacher with a steely stare while the guy exhausts himself with his bullying histrionics: That is the deeper resource I’ve always wanted to find—the still, silent center that I have brushed up against on a handful of occasions, only to watch it recede back into the depths; the ethos that belt levels mean nothing, that winning means nothing; it is all about the spirit with which one approaches an endeavor; I feel all of these things down to my bones. This movie speaks to everything that is earnest and good. It pulverizes cynicism.

Now, to get down to specifics:

Mr. Miyagi fixes Daniel La Russo in his gaze, his gruff stoicism giving way to tender emotion. Paraphrasing Bob Dylan (who said this of Mickey Rourke): That’s a look to break your heart; one of the most affecting movie moments I’ve come across in recent memory. It occurs when Miyagi gives Daniel one of his cars. All of the action comes from Ralph Macchio (Daniel) as he climbs into the car, cradles the keys in his hand, and tells Miyagi that he’s the best friend he’s ever had. But it’s Pat Morita’s face that becomes the focus of our attention. That steady gaze—that symphonic wash of emotion: It’s simply perfect. The crusty old mentor was a tired movie trope even by 1984, but God bless Pat Morita for his feat of alchemy—for bringing Miyagi not just into my heart, but also conjuring memories of my grandfather and my Japanese step-grandmother, and of their generation—which was still so very much with us in 1984, guiding us even still, and whose absence I miss so dearly.

As I discovered, though, The Karate Kid is by no means a home run (if I may mix my athletic metaphors). Like so many of the 1984 movies, its heart carries it over the finish line and, as I said earlier, obliterates cynicism. Yet, on reflection it becomes clear that the movie’s flaws are legion. So it is time for us to hold two opposing ideas in our heads—what Fitzgerald said was “the test of a first-rate intelligence”: On the one hand The Karate Kid is pure, blameless, almost a holy thing. On the other hand, it is an uneven film.

Most of the problems pertain to the central plot point of the tournament—both the build up to it and the event itself. First, we are to believe that Miyagi teaches Daniel the elements of a black belt (or at least enough to be competitive) over two months—a large portion of which seems to be taken up by having Daniel paint his house, sand his decks, and polish his cars. We see Daniel learning how to balance standing up in a boat, throw some punches, and perfect the crane kick: a realistic amount of development for two months of intensive training, but nowhere near the amount needed to go up against a couple of dojos full of ripped young men who have ostensibly been training with their drill sergeant-style instructors since early childhood.

Then there is the tournament itself. I have a hard time grasping the rules. Two of the Cobra Kai kids are disqualified for inflicting injuries (on the legs and, I think, the torso), but Daniel somehow wins the tournament by kicking his nemesis in the face. Overall, the potential for sustaining serious injury, paralysis, or death at the tournament is high. No padding, no face protection. Yes, things were a bit more rough-and-tumble in the 1980s, but still… it’s a stretch.

Last point: Daniel telegraphs his final move—the crane kick—to his well-trained antagonist (who looks like he’s holding up well enough before that, whereas Daniel can barely stand.) Well, the kick looks good anyway.

It is startling how abruptly most of these ‘80s movies end—which feels like a throwback (or the last gasp) of a trend that was popular in the ‘40s and ‘50s. (Orson Welles’ The Stranger comes to mind). Spielberg and Lucas tend to give us a good wind-down, but The Karate Kid, The Natural, and The Pope of Greenwich Village all practically cut off mid-sentence. At least with The Karate Kid there is a sequel.

And yet, can I feel anything other than love for this movie? Like so much else with my project, the golden glow of the era that birthed The Karate Kid carries it through—along with the obvious love and commitment displayed by its three principal stars. (Let’s not forget Elizabeth Shue as Daniel’s love interest, kicking off a dynamic career that will feature star turns in such varied films as Leaving Las Vegas and… Piranha 3D!).

June 29, 2020 / September 29, 2020

Notice the diverging dates above. The trains are no longer running on parallel tracks. They have been coming apart for a while, but I am now officially decoupled from June 1984 and the pressure to sync my dates. I will continue my journey through 1984, but it’s going to take longer than anticipated, and it will not line up with the 2020 months. We’re going to see 2020 move further ahead, while I continue to glide through July-December 1984 at a more leisurely pace. And doesn’t it make sense that the childhood year would take me longer to get through? Years did seem longer back then. Much like the Pevensie children’s visits to Narnia all those generations ago, time begins to elongate in one of the worlds while passing quickly in the other.

So 2020 pulls ahead. I’m barely following current events, but it’s a world I could scarcely have imagined even at the beginning of the year. We are back in Arizona, and I’m back on the road for work for the first time since January. Prior to heading to the airport yesterday, I had been lulled into a feeling of semi-normalcy. Sure, my social activities have been curtailed. Sure, I need to wear a mask when I pop over to the post office. But around the house, around the neighborhood, I’m breathing free air. We have the babysitters over most days; they’re not masked. I get together with two friends from the neighborhood on the back porch most Wednesday nights; we can see each other’s faces.

But it was a shock entering the airport yesterday: all the people milling around—big, teeming crowds of people jostling to board: That’s normal of course, but everyone is masked up. And on the plane: no meal service. And in the bathrooms, the infrared hand dryers are turned off for some reason. People are resilient; everyone is making the best of this. But we’re also fatigued. We’re all trudging through these days leading up to the election. Bob Woodward’s new book Rage, about the Trump presidency, is everywhere. But I’m not sure people are buying and reading it. Why would they? Want to get stressed out on your flight? Read a book called Rage.

Who are my fellow-travelers? I can’t see their faces. Their eyes take on an added importance. And on the rare occasion that a person lowers his or her mask, there is a jolt of surprise: The face never looks as I expected it to. Where do these people escape to in the secret spaces of their homes? Not 1984, I suspect. But I know they’re not staying put in 2020. Who in his right mind would?

Teetering between two timelines, a sort of woozy haze permeating both realities, I feel like I am pushing up against madness. That’s hyperbole; a feeling of disorientation comes up on me at a certain point in every longform project—that feeling of no going back; the only way out is through. And I want to push through fast, but I can’t. The difference this time is that real life is echoing this feeling: I want to push through to the end of 2020, but I can’t. Each day demands to be lived in, counted down to the last millisecond.

Next up: Part 7.