Listening to 1984: An Experiment in Time Travel - Part 3 of 12

Repo Man! Spinal Tap! Romancing the Stone! Jesse Jackson (again)! Meanwhile in 2020, a pandemic nearly shuts down the operation.

2024 Editor’s note: This March entry is a little spare, with good reason; at this point in 2020, a worldwide pandemic plus an unplanned move east nearly derailed my living-in-1984 adventure. But spoiler alert: I kept going, and next month’s word count will be back in the red. Because, folks, this one goes to eleven.

The story so far: Sometime in 2019, I had a premonition that 2020 was going to suck. So— I decided to spend the year re-experiencing my favorite year from my childhood: 1984. By "re-experiencing" I mean listening to the music, watching the TV shows and movies, reading the news magazines and books, and listening to "American Top 40" and "Newsweek on Air" week-in, week-out, in chronological order. Weirdness ensued. I kept a journal.

(Note: If you just came onboard and are thoroughly confused, start with Part 1.)

March 2, 1984 / March 2, 2020

Along comes Repo Man, and in terms of genuine rebellion, this is more like it.

I don’t get the sense of the director and writer coloring within the proscribed lines of the Reagan era like I did with Footloose. Repo Man is an authentic punk rock movie with a riotous punk rock soundtrack. As is often the case in 1984, the strokes can be broad: the Christian caricature parents, the Harry Dean Stanton character spouting off against commies and deadbeats who don’t pay their bills, and the actual-aliens-in-the-trunk subplot that feels shoehorned in—but this thing is alive; it is defiant. There is life outside of the ‘80s mainstream and, weirdly, Emilio Estevez is part of it.

Repo Man bristles everywhere at the claustrophobia of the monoculture. Characters sing commercial jingles Tourette’s-like, as conspiracy monologues swell the screenplay. I’m not sure if it stands for anything more than nihilism, but it’s something.

And— look what else is out on this day!

No one—and I mean no one—who embarks on a life in rock ‘n’ roll can outrun the spooky reach of This is Spinal Tap, Rob Reiner’s inspired mockumentary that somehow captures the story arc of every band ever. Case in point: The members of U2, who you’d think would have been financially cocooned from all possible mishap by the mid-1990s, found themselves trapped together inside a giant mechanical lemon on multiple occasions during their 1997 PopMart tour. (In retrospect, the hubris of going on stage in an oversized lemon, knowing full well of the existence of the pod scene in This Is Spinal Tap, is tantamount to a cocky young actor saying, “Wish me luck with my upcoming performance in…Macbeth!”)

This is Spinal Tap reveals, accurately, that the rock life is often undignified and clownish. Paradoxically, only those who shrug their shoulders and laugh along will get anywhere in the neighborhood of dignity. Those who don’t will be eaten alive. I repeat that no one escapes. Latter-day bands like Fugazi and Rage Against the Machine, who made ostentatious stands against the clownishness, inevitably became clownish in their defiance.

Has an entire category of artmaking ever been so expertly pinned? By all rights, This is Spinal Tap, ostensibly a work of fiction, ought to have walked away with the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature. But why stop there? At this point in my journey, it is the one to beat for best overall movie of 1984.

March 3, 1984 / March 3, 2020

Even though “Everybody’s got a bomb, we could all die any day” (as Prince sang in “1999”), the party roars on in the 1980s.

So how to explain the dank and dreary 1990s, when we really ought to have been throwing the party? Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Alice in Chains all sludging up the airwaves, and Jerry Seinfield scoring big laughs with cynicism, irony, and insincerity. Serial killer movies everywhere, and weird throwback obsessions with alien abductions and the Kennedy assassination. The Berlin Wall just came down and the Soviet Union has finally been vanquished—peacefully. So what the fuck is wrong with you guys?

Maybe Armageddon’s reprieve gave everyone the luxury to sulk? Like when a child puts on a show of easygoing confidence during the school day and then melts down in the safe environment of home.

Anyway, it wasn’t all bad. I liked those grunge bands individually. I loved Seinfeld. But I think Mickey Rourke got it more right than wrong in his bar scene with Marissa Tomei in The Wrestler. (Fittingly, the song that inspired this exchange is a 1984 track: “Round and Round” by Ratt):

Tomei: “Fuckin’ ‘80s, man; best shit ever.”

Rourke: “Then that Cobain pussy had to come around and ruin it all.”

Tomei: “Like there’s something wrong with wanting to have a good time!”

Rourke: “Let me tell you something, I hated the fuckin’ ‘90s.”

Tomei: “’90s fuckin’ sucked.”

Rourke: “’90s fuckin’ sucked.”

March 18, 1984 / March 18, 2020

Coronavirus pulling me out of 1984. Epidemics in both timeframes: Corona in 2020, AIDS in 1984. Only— in one timeframe the government is directing all its resources at the bug, shutting down restaurants, schools, everything. Because— old people could get it and die. In the other timestream, there is almost zero acknowledgment from the highest levels of government. Because— gay people could get it and die?

Granted, the methods of transmission are very different. You can go out in public in 1984 with zero risk of contracting AIDS, even if you stand in close proximity to someone infected. But still, what a difference in media coverage. In 2020, when it is revealed that the disease primarily affects the elderly, there is widespread concern and immediate action. In 1984, when it is learned that the disease primarily affects gay men and intravenous drug users, there is undisguised relief.

And yet, the timestreams continue to fold over each other. Two hits of 1984 send their messages to me in 2020: John Lennon’s posthumous single “Nobody Told Me” (“Nobody told me there’d be days like these / Strange days indeed.”) And, as state-by-state lockdowns begin to be enforced, Rockwell’s “Somebody’s Watching Me” continues its implacable climb in the alternate timestream.

*****

I am tuned in to the March 18, 1984 Democratic presidential debate in Chicago, where racial injustice is on the table. The accusation is that the Reagan administration has left the concerns of minority communities behind in its rush to supply-side the country back to economic health. Candidate Jesse Jackson is keeping the concerns front and center, but there is irony in the number of racist jabs—unconscious but blatant to my 2020 sensibility—he must endure in the ostensibly friendly environment of a Democratic Party debate. I am impressed by his graciousness and easygoing humor when a moderator makes a gaffe about Jackson being “a dark horse”—which causes some in the audience to gasp audibly and Jackson to wince for a split second. But then, without missing a beat, Jackson says, “I’m a dark horse no matter how you—” (Audience breaks in with laughter as Jackson cracks a grin). “But that’s not the point. And I have no apologies about this horse. You know, it’s not about whether it’s dark or light, it’s a good horse; it’s a fast horse; and in South Carolina it was a winning horse!”

Throughout the debate, I get the feeling that people are humoring Jackson but not taking him seriously. His qualifications are brought into question: He is a Reverend and a civil rights leader; on what grounds can he weigh in on “industrial issues.” This despite the fact that he has obviously done his homework and is bringing some stimulating outside-the-box ideas to the conversation. And on foreign policy—as I noted before, the guy got a hostage freed from Syria. What more does a person need to do in order to be taken seriously? If Gary Hart had gone off and freed a hostage, does anyone doubt that he would have instantly become an acknowledged Subject Matter Expert?

I will concede that Jackson is a showboat; he has that over-the-top Southern preacher style, which I rather like, but which comes off as contrived next to Mondale’s “let’s get down to the essence of things” approach. Still, the man they are trying to defeat—Reagan—is nothing if not theatrical. It’s a bit of a shame that the Democratic rank-and-file did not roll the dice on Jackson in 1984, a much larger shame that rolling the dice on Jackson was never taken seriously as an option.

March 30, 1984 / March 30, 2020

The years have not been kind to Romancing the Stone. It’s not terrible by any means, but it is terribly dated. I’ll stick with the positives for the moment: the great chemistry between Michael Douglas and Kathleen Turner. Not for nothing did they go on to make two more films together. In ‘84 Turner was already a big name courtesy of Body Heat, but, even though Douglas had been toiling at his trade since the 1960s and had had substantial success as a producer, “Lil’ Kirk” (which no one called him ever) was still a largely unknown quantity for mass audiences. He’s a terrific actor, as the world would discover, and he’s terrific in Romancing the Stone, but he’s still a distant third behind Jack Nicholson and Harrison Ford at playing this sort of rascal antihero. With Nicholson he shares a sleazy energy—a combination of swagger, wolfishness, and a knowing look in his eyes. But unlike Nicholson, he doesn’t seem entirely comfortable in his own skin. There is a subtle creepiness around the edges that, in coming years, will give him a tremendous edge playing villains and morally compromised characters, but will always make him a slightly challenging romantic lead.

I loved Romancing the Stone in the ‘80s. Granted, it’s Raiders of the Lost Ark-lite, just one representative of a crowd that included the TV shows Tales of the Gold Monkey and Bring ‘Em Back Alive and the movie High Road to China (starring Tom Selleck). Still, it’s a hell of a lot better than Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (forthcoming in 1984).

But those jokes: “Goddamn it, I knew I should've listened to my mother. I could've been a cosmetic surgeon, five hundred thou a year, up to my neck in tits and ass.” This from Douglas during a harrowing chase scene. (Maybe the career-spanning creep factor had its origins in this moment?)

Further demerits: the grating banter between Danny DeVito’s two-bit criminal and his cousin Ira; the terrible music by Alan Sylvestri—everything bad about ‘80s synths and quantization and nothing good (though the Eddy Grant theme song, barely used in the movie, has aspects of greatness); the South American racial stereotypes; the damsel-in-distress aspects of Turner’s character. This is very much a product of 1984 and not a year later.

Still, one moment in the movie sticks with me. Digging for the ruby—the “stone” of the title, Turner turns to Douglas and says, “Jack, you’re the best time I’ve ever had.”

Douglas: “I’ve never been anyone’s best anything before.”

The pathos of that delivery—from the son of a famous actor, who has been slogging away and, despite his considerable achievements, has never been taken seriously or given a shot like this; the action hero not completely at ease with himself—it’s moments like this make Michael Douglas great, make him and Kathleen Turner great together, and make me happy the movie exists.

*****

As 2020 darkens, clouds gather in 1984 also—at least in England. It’s clear that 1984 was a different experience in the UK than in the US. While nuclear fears informed the pop music and entertainment of both countries, those fears must have seemed more immediate in the UK, with the Iron Curtain in closer proximity and the home front riven with labor unrest and the harder tone of the Thatcher administration.

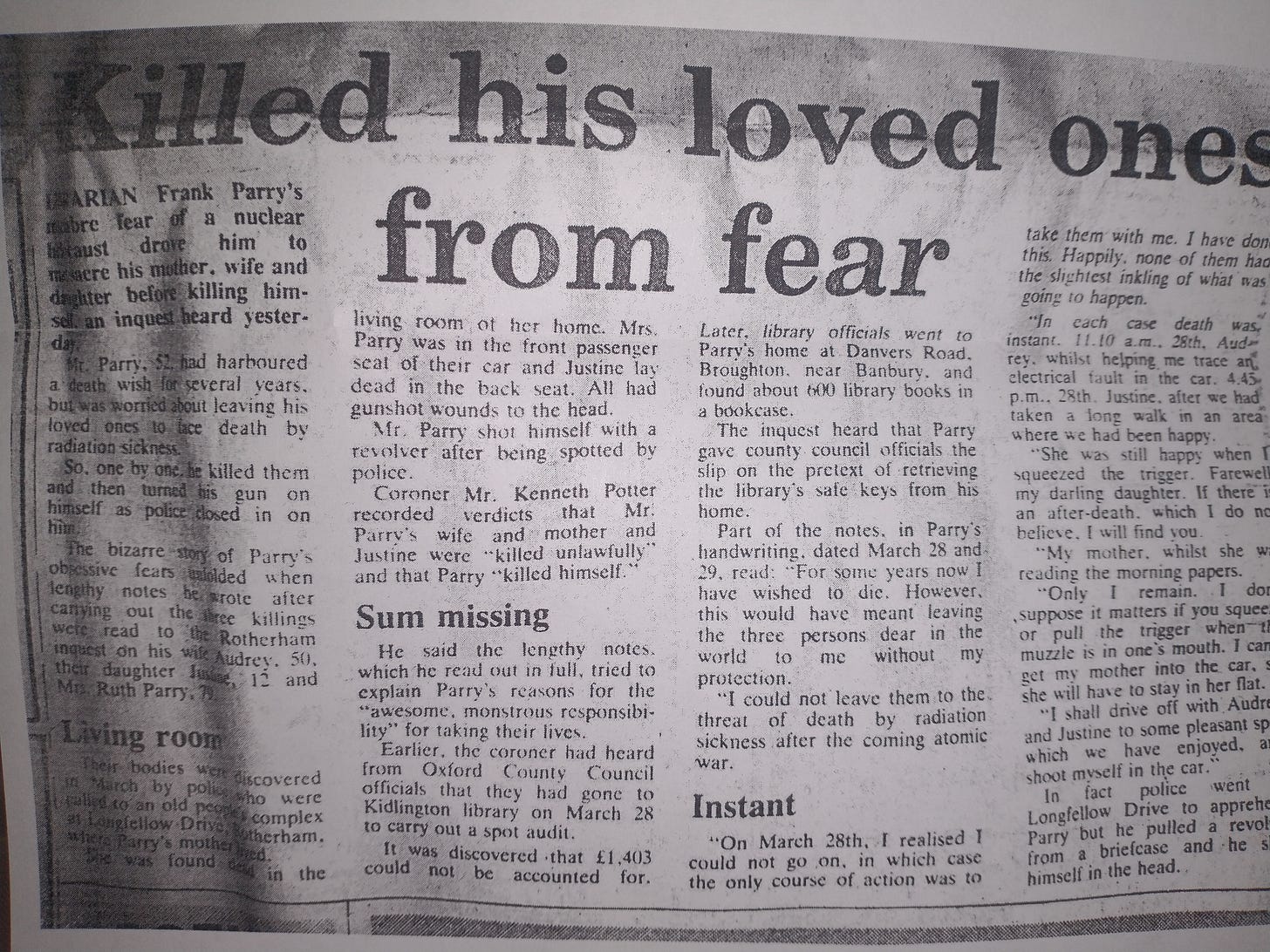

This from a UK newspaper uncovered among a late family member’s possessions: On March 28-29, 1984, a mentally unstable 52-year-old British man methodically shot his daughter, wife, mother, and them himself, leaving behind a note explaining that he had done all this to spare his family an agonizing death from radiation fallout in “the coming atomic war.” Should this event be considered collateral damage of the ongoing US-Soviet brinkmanship? Only in the sense that a deranged mind will often find a current event or something in the media to latch onto. But reading excerpts from his letter, in which his cold descriptions of each of the killings wrestle on the page with unsettling moments of intimacy—“my darling daughter,” etc.—it seems obscene to blame anyone other than this man. Whenever I am confronted with these types of news events, it is made jarringly clear that we are missing some pieces— of how the world works, how human beings work, how God works if he/she/it exists. Every religion posits explanations for evil: diabolical interference, selfishness, distance from God, spiritual disharmony. None are satisfactory. We lack the manual. At best, the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the handbook of the American Psychiatric Association) amounts to smeared cave paintings.

This event is a cold shower on my nostalgia for a supposedly gentler era when things made more sense.

Next up: Part 4.

A tip of the hat for mentioning Tales of the Gold Monkey. I loved that show as a kid. When internet finally arrived at my university, the first things I looked up were Tales of the Gold Monkey and The Church.