Holding out for the Roses

The Story of Dayroom

For my Substack debut, it feels appropriate to feature an underrated Athens, GA band that was DIY from start to finish.

I.

I’m living by and large in the back of a beat-up car

This way I’m always close to home

Come over anytime, we’ll open a bottle of cheap wine

And wake up stinking like a Wild Irish Rose

The young guitarist looks out over a packed theater, seeing the faces of friends, strangers, and the murky multitudes in between, all pushing forward toward the stage. Is there anyone in the place not singing? To his right, the keyboardist channels Dr. John, Scott Joplin, and just a touch of the giggling psychopathic pianist in Reefer Madness. Before long, the song’s signature hook kicks in and the guitarist and the bassist propel themselves toward the rafters, as if the floor of the Georgia Theatre has become a trampoline. The drummer implacably drives this much-abused train toward its final destination. Within minutes the crowd—as many as can manage—will be on the stage, erasing the thin membrane between Dayroom and its fans. None of the musicians wants to stop playing, and so each will end the song in a different place. And in the melee that follows, the singer’s cherished vintage white jacket will be trampled to threads. It is the end of many things.

Did it really happen?

Michael Winger, the singer-guitarist, may come to ponder that question in the days and years to come, as the ground stops moving beneath his feet but the images continue to gallop through his brain: the giant inflatable gorilla; the “Nuclear Wessel”; the praying mantises; the bright red Chesterfield Café sign in Madrid; the lake of human feces; the infinity nosebleed; the time when the steering wheel of the tour van came detached from the dashboard, prompting the drummer (who was driving) to turn to his bandmates and say, “Guys, this is bad”; and— ever present, the miles and miles of flying spinning careening road. A tangle of memories and legends and dreams culminating in Dayroom crashing to shore with an undertow of “what if?” dragging Michael back to sea.

Real life, almost a decade deferred, stretches ahead.

II.

Roughly nine years earlier, Winger—long-haired, slight-of-build, sartorially challenged—angled his guitar amplifier toward the window of his Oglethorpe (“O-House”) dorm room and let fly some Hendrix-style riffs over the parking lot. It was 9AM on game day, when inebriated middle-aged alumni chanting “Go Dawgs! Woof! Woof! Woof!” routinely overran the University of Georgia’s north campus. Mike fantasized that his fretwork would annoy this horde, but it only added to the collective frenzy.

The guitar volley had become a ritual, and while he never got much of a reaction from the football fans, on this particular day a hallmate dropped by and told Mike of two friends—UGA students from Atlanta—who were looking to form a band. And just like that, in a single chance conversation, the remainder of the 1990s zipped itself up for Michael Winger, Brad Lee Zimmerman, and Jimmy Riddle. They christened their project Dayroom, after a Don DeLillo play in which, as Winger puts it, “the lines are blurred between who is the doctor and who is the patient.” Zimmerman (drums) and Riddle (keyboards) recruited a friend from their high school days named John Buzzell to play bass—a wonderful musician but allegedly a horrific driver (a personality trait that would get immortalized in the song “Johnny Can’t Drive”).

Winger was an honors student in history, following a family tradition. His specialty: Chinese and Cuban communism. He continued on with his degree, but his schedule now had to accommodate four-hour band rehearsals. The group operated under the same “we’ll just see what happens” ethos as many of the other bands around Athens, Georgia, but the members’ pedigrees were a cut above. Mike had already spent a couple summers teaching at the National Guitar Summer Workshop and counted Adrian Belew as a friendly acquaintance. Riddle, Zimmerman, and Buzzell were similarly seasoned on their instruments. Everyone had been in bands before. Dayroom endured no apprenticeship phase of three-chord bashers; the group started with Zappa and went from there.

This may explain why, not too long after its live debut in spring 1992, the band secured a dedicated manager in cherubic, red-headed Troy Aubrey.

“My earliest memory was seeing the band at an old venue/bar called the Flying Buffalo in Athens,” Aubrey says now.

I believe it was an open mic night with various young bands playing. At that show I was completely captivated by the band’s eclectic sound. The songs were crazy…. and Mike Winger was a standout guitarist ripping solos and whacked out guitar riffs. Solid drumming by Brad, fun basslines by John Buzzell, and the secret weapon was Jimmy Riddle on keys and backup vocals. It was wild and I was instantly impressed and interested in working with this incredibly versatile band. It was like listening to a Zappa, Phish and Talking Heads mashup.

We can add to Aubrey’s account that rubber chickens were involved. An early song, “Feel Like a Nut,” (channeling a ubiquitous Almond Joy / Mounds commercial) captures something of the spirit of the enterprise:

Smearin’ Crisco on a baby gerbil

Watchin’ it squirm like a Ninja Turtle

Never had to be wishin’

To shove it in the ass of a politician

…..

Sometimes you feel like a nut

Sometimes you don’t

Gonzo songs such as this one and “Losing My Marbles,” in which the love-stricken protagonist drifts into a romantic entanglement with a cow, coexisted precariously with “Twenty One Times” and “Heaven,” songs of longing and loss that blended elements of R.E.M. and CCR with more than a little Winger-centric darkness.

The Athens, GA music scene found itself in an interesting space in the early 1990s. After that first attention-grabbing wave of bands—you know their names: the B-52s, R.E.M., Pylon, Love Tractor—blew through a decade earlier, an infrastructure of clubs, local press and industry backchannels had emerged to nurture the scene. At the same time, the wider world shifted its gaze to Seattle. In a way, this proved fortuitous for the new bands: they could benefit from the resources put in place by those successful forebears without wilting in the unforgiving glare of a national spotlight—at least not right away.

Some strong artists appeared during this era, among them Vic Chesnutt, Five Eight, Porn Orchard, Seven Simons, and the Violets. Bob Mould’s band Sugar, which featured local bassist David Barbe, used Athens as a launching point. And Widespread Panic extended a bridge back to the Southern rock that so many in Athens’ first wave had assiduously rejected. Was there room in this melting pot for Dayroom, a group that managed to blend a number of qualities exemplified by the artists above? Yes—eventually. But Dayroom took detours, becoming, for a time, an 80’s cover band: a bold move when the door had barely closed on that decade. An early promotional document circulated by Aubrey highlighted the group’s specialties during this period: “Rio,” “Down Under,” “Like a Virgin,” Our House,” “Electric Avenue,” “Der Kommissar,” “Come On Eileen,” “and other ‘80s and MTV favorites.” Even after they shifted back to mostly original material, Zimmerman quipped that Dayroom was “an ‘80s band that missed the ‘80s,” speaking not so much to the group’s sound but to its exuberance, so out of step with the self-seriousness of the grunge era. If the ‘80s had been a raucous party with the ‘90s serving as its head-splitting hangover, the members of Dayroom were still at the after-hours bar, holding off the grey dawn.

They played incessantly, but mostly on weekends (which unofficially began in Athens on Thursdays) and during school breaks. Dayroom’s 1993 cassette album Twelve Dead Snakes made some local waves—especially its cover image: a painting by Michael’s father of a suited businessman with his detached head rising up, balloon-like, from his collar. “Floating Head Man” was all over Athens in the 1990s—on tape covers, concert flyers, and T-shirts. Not everyone in town attended a Dayroom concert, but everyone saw that painting.

After a money-losing string of shows in New York, John Buzzell bowed out. The very capable Carl Lindberg stepped in to play on Dayroom’s 1995 CD debut Perpetual Smile and some subsequent shows, and then he too moved on. But just as it began to seem that the bass-player slot in Dayroom had become analogous to the drummer’s role in This is Spinal Tap, in stepped Ryan Kelly to solidify what became the group’s classic lineup, just in time for Riddle, the last member still in college, to complete his degree.

III.

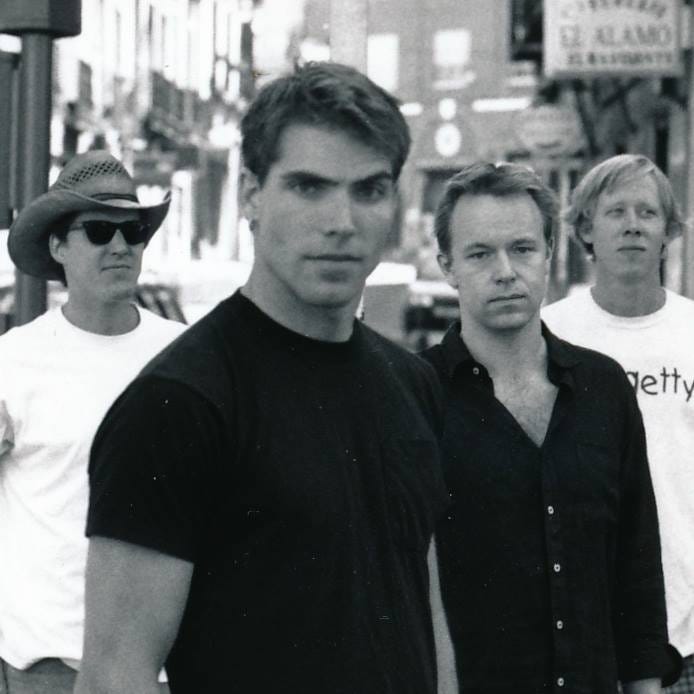

Let us pause at the brink of Dayroom’s first “proper” tour in support of its first “proper” album to examine our fab four in greater detail. We have the conspicuously handsome Zimmerman, with cheekbones seemingly hewn from granite, who would often add insult to injury by performing shirtless. Putting him in Dayroom was akin to parachuting Cary Grant into the lineup of Drivin’ n Cryin’, though Grant (to the best of this writer’s knowledge) never had the nickname “Nookie Dong” attached to him. A Journalism and Communications major at UGA, Zimmerman became, alongside Winger, an effective spokesperson for the band. He was also an exceptional drummer, nimbly hopscotching across styles.

Michael Winger was not without his own assets, flaunting a Jack Nicholson grin and an extroverted stage persona—a contrast to his actual personality, which leaned toward introspection. How to reconcile the surreal goofiness of Dayroom’s image with its principal songwriter’s downbeat view of humanity? Sometimes you feel like a nut, sometimes you don’t. Winger’s guitar style exhibited similar polarities: although an ace player and a riff machine, he rarely indulged in lengthy solos.

Riddle, lanky and boyish, unmistakable for his mop of bright blond hair and piercing eyes, had a growly speaking voice that weirdly paralleled Winger’s rough singing voice. (Winger, in turn, had a soft, lilting speaking voice that echoed Riddle’s sweet and pure singing style). As a keyboardist, his arsenal of styles included New Orleans funk, Ragtime, Jerry Lee Lewis-style rock ‘n’ roll, and new wave.

Finally, Ryan Kelly of Statesboro, GA—scion of a family that included Emma Kelly, the “Lady of 6,000 songs” immortalized in John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil; easygoing with a sweet grin and lazy drawl—was the band’s natural comedic foil. From a musical standpoint, Jaco Pastorius would not have been ashamed to be in a room with him. And, indeed, Ryan came into the band playing (like Pastorius) a fretless bass and moved on to the intimidating Alembic Essence 5-string. His dexterity across the expanded range of this instrument, and his wide musical vocabulary, set him apart from many of his contemporaries.

So, with the principals introduced, it’s time to cue up Perpetual Smile’s “Holding Out for the Roses” for our tour montage. (For those readers who don’t have ready access to a speaker, imagine a rapidly strummed Am, F, C, G, F, C, G, Am, F, C, G, Am, G, F with earnest, rootsy vocals.)

She’s holding out for the roses…

Fade-in to a battered cargo van tearing across the Southeast. This is the “Nuclear Wessel,” named for a Chekhov quote (the Star Trek character, not the Russian author). Crossfade to the van’s interior. We see that all the seating has been removed save the front two pilot seats. Winger is lying face-down on the floor, gazing through the holes where the chess table was once bolted in, watching the road fly by underneath him.

The van abruptly slows. Zimmerman has to lean back hard against the speaker cabinets that are serving as his backrest, lest they go flying forward and cause grievous bodily harm.

Waiting to feel the sweet thorn in her hand…

Fade to a gas station in Arkansas. Riddle is filling up the van. Road manager Kyle speaks animatedly into a pay phone several feet away, explaining to the club owner that the band is on the way. He listens intently, then shouts a question to Riddle: Did they make such and such a turn yet? Riddle responds. Kyle talks some more to the owner. Shouts again to Riddle. Did they make such and such other turn? Riddle, out of exasperation, exhaustion, the weariness of I don’t know where I am; I have lost all sense of time and space and being; and I don’t know what day it is and I’m working hard to hold onto the year; and—this is important—I don’t know who the hell Kyle is talking to, or why he’s asking me about the turnoffs—yells back, “Who gives a shit?”

Pause. Kyle listens intently. Four words ago, they were on their way to Joplin, Missouri. Four words later, they’re turning the van around, disinvited.

Holding out for the roses…

Fade-in to a motel parking lot somewhere in Texas. The “Wessel” peals out, screeching and throwing gravel in its wake. Dayroom is on the run from a sheriff’s deputy for (kind-of sort-of) accidentally “defrauding an innkeeper.”

Voiceover of Riddle: “There wasn’t an Internet so we could stay ahead of the law with pure speed.”

Fade-in to a cramped studio apartment in Lawrence, Kansas. The Dayroom boys sleep side by side on the floor, crammed together like sardines, Winger’s face pressed against an aquarium filled with praying mantises. (The apartment’s owner—a friend of the band—studies entomology at U Kansas). A gentle rhythm of snores and wheezes rolls up and down the room. Tight-focus on Winger drooling onto the aquarium glass.

Suddenly, Zimmerman sits bolt upright and says in a deep voice, “I want you and your miserable friends out. I will destroy you all in one fell swoop.” He collapses back into the arms of sleep, leaving his bandmates awake and disoriented.

Crossfade to a sparsely populated venue in Steamboat Springs, Colorado. Winger leans in a little too quickly to the mic, hits it with his nose, and the abrupt contact coupled with the elevated altitude causes a geyser-like nosebleed. The band plays on.

Never let a man let her down again

The whole thing was absurd. A band just beginning to make a name for itself in its hometown and surrounding environs books a tour out to Colorado by way of Texas, Mississippi, Arkansas, Kansas, and a host of other random, zigzagged locations. Because…Riddle and Zimmerman wanted to go skiing. And so Aubrey dutifully lined it up, club by club, over the phone (Because—no Internet, or at least no Internet that would have been of any use here). It made zero business sense, and there was virtually no way Dayroom could hold onto what audience it managed to pick up on this Quixotic quest. And yet, did it make business sense for the Beatles to go off to Hamburg in their early days? Maybe not, but they came back as The Beatles. The Dayroom tour had a similar result. “Maybe there was something to going out and doing all those shows and coming back to Athens as this road-tested band,” Ryan says. “Rather than them seeing us grow like grass, we go off and come back like a huge weed.”

The touring continued, but closer to home. Fans’ names and addresses were dutifully recorded. The Dayroom snail-mail newsletter launched, initially going out to hundreds, then thousands, of honest-to-God fans. Town after town, the band seized ground and held it. And on each return trip to these towns, the audiences grew. The fans had told their friends. Those friends became fans. They told their friends.

Dayroom logged approximately 200 performances in 1995, then another 200 the following year. The group played anywhere and everywhere: clubs, restaurants, frat parties. It was all DIY—the mailouts, the albums, the T-shirts. Perpetual Smile went into heavy rotation on the popular Atlanta rock station 99X and was voted “Album of the Year” on the “Locals Only” program—an astonishing feat given that the album initially changed hands mainly at shows and via consignment sales at independent record stores. Record labels were barely aware of this growing ecosystem, and the ones that became aware just didn’t “get” it. But audiences got it immediately. The music sounded great, you could dance to it, the band was on fire, and these four guys, collectively, had the charisma of some of the greats. Everyone except the record labels was rooting for them. Bruce Springsteen once said that U2 was the last rock band of whom he knew all four members’ names. But for thousands of music fans in the Southeast in the 1990s, that description might rightly go to Dayroom. Indeed, for some, Dayroom may have been the last rock band.

IV.

Can’t hear a word at all

There’s a TV up on every single wall you see

The fever it rages

Everything you say

Everything you say is contagious

Something was stirring in the mid-1990s. Mike Winger sensed it, though what he perceived to be a conflagration was simply the preliminary kindling fire. Over time, that fire would surge to the proportions of his vision, revealing the songs he wrote in 1995-1996 to be arguably more relevant to the 2020s than to the era in which they were composed. The specific impetus for the song “Contagious,” quoted above, was the birth of the 24-hour news cycle (via CNN) and the immediate need to sensationalize in order to fill those hours with eye-grabbing content. And side-by-side with that development was the ascendance of talk radio, a topic which the song “My Way or No Way” took on directly. The lyrics do not mention Rush Limbaugh by name, but he was the inspiration. “It’s my way or no way!” howl Winger, Riddle, and Kelly over a crushing wall of noise. Winger had previously referred to Dayroom as a “counter-grunge” band, but this song could slot easily onto a Pearl Jam album—though there is something distinctly Dayroom about the bizarre shadow chorus, in which the three singers abandon the lyrics altogether to chant “Yum yum! Yum yum! Yum yum!” Mike explained to 99X’s Steve Craig that this was his “interpretation of Rush rolling around in pig fat.” He elaborated on this theme during a 1996 Athens performance, instructing the audience to imagine Rush Limbaugh and Jay Leno wrestling in lard wearing “sumo diapers.”

The themes of paranoia and toxic media carry over into “Wait a Minute,” where they collide with more personal concerns. Winger told his friend (and band legal advisor) David Prasse that the song was a reaction to his parents’ divorce. But in this narrative of a bitterly unhappy couple spiraling toward their demise, technology serves as the brain-numbing backdrop:

I want to veg’ in front of a wall of machines

How’d I know that your caged bird’s never gonna sing

Go and do your own thing

We grew up fast- We found out quick that nothing lasts here

We grew up fast- You hold my hand and you let me pass out

We grew up fast

Another song, “Time Bomb,” picks up the toxic relationship thread, while working in images of a breaking-down car and the titular incendiary device.

Interspersed with these black-as-night musings are a couple of hookup songs: “Come on Over” and “Lying Awake,” but given the bombed-out surroundings these feel like sex during wartime. Two other songs, “New Year’s Eve” and the regional hit “Cheap Wine,” split the difference: hedonistic exuberance with the nagging feeling that all might not be as happy-go-lucky as it seems.

Winger’s vocals, always rough-hewn, became downright frantic on Contagious. “I had to drive through heavy Atlanta traffic on the way to the studio,” Winger says. “And the deeper I got into Atlanta, the more claustrophobic I felt. That definitely came through in the performance.”

And yet, the insidious brilliance of the Contagious album (recently reissued on vinyl by Slush Fund Recordings) is that the actual music, except on “My Way or No Way,” cuts hard against the darkness. Winger had been getting heavily into funk, and that influence, along with jazz, disco, and Southern boogie, informs much of the playing. The great Australian songwriter Steve Kilbey once described the technique of combining upbeat music with downbeat lyrics as “a clown coming at you with a hand grenade.” In this case the sound of the music, along with Dayroom’s relentlessly fun and upbeat shows, caused a good number in the audience—along with some critics—to miss the grenade entirely. Dayroom continued to be characterized as a “fun-loving band,” which was not an untrue statement—but also not a complete one.

No matter. Contagious swelled the fans’ ranks. And “Cheap Wine” became one of the most requested songs on 99X and went into rotation on a number of other stations in Georgia and elsewhere. And for the second consecutive year, Dayroom won the prestigious “Album of the Year” prize on Locals Only.

V.

Honestly, we just don’t hear either of the new songs as being that career-launching breakthrough hit we’re looking for. ‘Cheap Wine’ is still our favorite, but we don’t think it’s quite there, either. Regretfully, we’ll have to pass.

-1998 letter from a record label to Troy Aubrey, after reviewing selections from Contagious.

It seems like a no-brainer: Band approaches labels with a ready-to-go fanbase numbering in the tens of thousands, a proven track record selling out prestige venues across a wide geographic region, and a couple of actual hits on mainstream Southern rock radio already under its belt. Why Dayroom didn’t receive serious attention and consideration from the labels, especially given some of the sludge that did get funded during the last great rock signing spree of the 1990s, remains a mystery.

“The labels just didn’t get it,” Troy Aubrey says with a sigh. “It wasn’t through lack of trying on our part. But it was hard for the labels to grasp something that was so eclectic. You know, it’s not college radio, but it’s not Phish either.”

In the history of the Dayroom ascent, with obstacle after obstacle surmounted, major labels remained the only holdout. Audiences had never minded that the band was “difficult to define.” Dayroom was simply “good,” and in the final analysis, is any other adjective needed? From 1996 onward, concert venues in the southeast didn’t need convincing; attendance figures did the trick. At these shows, Dayroom’s merch sales often equaled or exceeded the haul from ticket sales. Beyond the clubs and theaters, the band easily secured slots at 99X’s Big Day Out and Atlanta’s Music Midtown. They played South by Southwest. And the days of Aubrey needing to book the tours by himself, venue by venue over the phone, were long gone. Agents arrived to handle all that. By the close of the decade, Redeye Distribution took the burden off of Aubrey’s byzantine but scrupulously managed network of consignment agreements.

It was an impressive operation, one that was capable of turning a profit. Dayroom had been a mostly full-time job for Zimmerman, Winger, Riddle, Kelly, and Aubrey since 1995. But it became clear as the decade neared its close that a plateau had been reached. Either someone or something needed to swoop in, Deus ex Machina-style, to lift things to the next level, or the band had to make one more herculean push and hope that was enough. And was such a feat even possible, after nearly four years of nonstop activity?

Better Days was part of that push. After working with the very capable Don McCollister, first in an engineering capacity on Perpetual Smile and then as producer on Contagious, the band decided to enlist John Keane to helm the third album. Best known for his extensive recording history with R.E.M., Keane “kicked our asses,” in Zimmerman’s words, challenging the band to pare things down to the bare essentials. The focus on this outing would be 100% on the songcraft, with the group’s well-known musical virtuosity held back for the concert stage. “He took the busyness out of my playing,” Riddle affirms. The end result: Dayroom’s best album, if also its most conventional. It’s the one Dayroom album that stands fully on its own, that does not rely to some degree on the added energy of subsequent live performances to close the circuit of its songs.

For Winger especially, the record was a triumph. He dialed back the outward-facing anger of Contagious and, apart from the magnificently angsty “Crazy” (which dated from the 1996 tour), his relationship songs were more wistful than accusatory. He sang in a more controlled style. Not for the first time, he was mining the slow downward trajectory of a relationship, but there was an added factor in the mix: “I didn’t realize until later that I was also writing to the band,” he says. Thus, lines like “Still a long way from home / Still don’t know where we are” (from “Stranded”) and “I won’t close my eyes and hope that all this goes away / I’ll just say that I’ve had better days” (from the title track) take on added meaning.

The album was also a breakthrough for Riddle, who wrote and sang two songs: the playful and offbeat “Condo” and the instantly catchy “Day by Day.”

Better Days is subdued and beautiful. It’s an appropriate final album, peppered with hints of the approaching wind-down—because history forces us to find them there.

VI.

It was like Mad Max…with patchouli.

– Ryan Kelly.

There is no Dayroom song appropriate for our Woodstock ’99 sequence. So we’ll go with… oh, why not? “The End” by the Doors. Play it in your head and picture the following:

Overturned garbage cans. Nonresponsive bodies lying amidst the strewn waste. Zombie-like figures with leaf-blowers walking through the mist. A dull, monotonous BANG…BANG…BANG…BANG as concertgoers, bombed out of their minds, pound on the overturned bins. In front of the non-functioning portable toilets, a pond—no, the imagination renders it a lake—of human feces and urine spreads ever outward. No one would be surprised to hear the whup-whup-whup of helicopter blades overhead as a young Martin Sheen emerges from the lake’s depths clutching a dagger, on his way to slay Colonel Kurtz. Or wait—that’s not Martin Sheen. It’s Ryan Kelly, and he’s going after John Entwistle.

Let the record be clear: Dayroom never did play Woodstock ’99. But the band had been invited to perform on the Emerging Artists Stage—one of only four or five unsigned acts to receive this honor—and our heroes seized the opportunity. Woodstock! Maybe this is the thing to break it wide open! They arrived at the concert site in Rome, New York after an all-day and all-night drive, seeking fame, glory, and bragging rights. (Cash was not in the offing.)

“The first thing I experienced was a hangar filled with passed-out ravers from an all-night dance party the previous night,” wrote Dayroom’s tour manager Kip in a retrospective account of the experience. Observing the grounds crew weaving around the bodies with their leaf-blowers, Kip remembered “wondering if these people were dead because you have to be seriously knocked out to sleep through blowers just feet from your head.”

It was also not a good sign that the band had been greeted by “a stage crew that weren’t really sure who we were or why we were there.”

After some inquiries were made, it was learned that the band had been bumped from its timeslot because John Entwistle (of the Who) had arrived at the festival unannounced and wished to play. The organizers had nowhere else to put him, so they gave him Dayroom’s slot—on the Emerging Artists Stage. (Let that one sink in.)

Winger and Kelly remember watching Entwistle glide by, wraith-like, a tall man on spindly legs, adorned with a “Boris the Spider” necklace. There he went—“The Ox,” only three years away from his demise, clinging to his narrow cliff ledge of relevance even if it meant (inadvertently) cock-blocking Dayroom from its shot on the national stage.

“John Entwistle is kind of the first bass player you knew the name of,” Kelly says. “And I just remember being a few feet from the guy and part of me is in awe and part of me wanted to slug this guy.”

Some further attempts were made to claw victory from the jaws of defeat:

Another band had not arrived, so the members of Dayroom unloaded their gear and prepared to take the stage in that band’s slot. But at the absolute last second, the missing band showed up and the gear had to be loaded, piece by piece, back into the van.

The festival’s “Cyber Café” was mooted as a possible place to do a sort of “pop-up” performance. But a quick inspection revealed an abandoned tent filled with desktop PCs that had been overturned and urinated on.

Busking was ruled out because of the incessant BANG! BANG! BANG! of the wastrels pounding on the overturned garbage cans.

At a certain point, Brad gave his tap-out signal: “Guys, this is bad.”

They rolled out of Rome Sunday evening, Brad and Kip strategizing furiously about “damage control.” If they had glanced in the rearview mirror, would they have seen the fires burning behind them?

Yes, actual, non-metaphorical fires. Pushed to the breaking point by a variety of factors—extreme heat, lack of sanitation, lack of adequate security, price gouging on food and water, and set after set of relentlessly aggressive music from the likes of Korn, Limp Bizkit, Metallica, and the Offspring—some in the crowd were ready to take the place apart by the time the Red Hot Chili Peppers took the stage that final night. And some of the candles that had been provided by a well-meaning nonprofit group for the purpose of commemorating the Columbine massacre got put to a different use.

Riot police arrived shortly thereafter.

Bands break up for a variety of reasons: money issues, creative differences, exhaustion, dysfunction in the members’ personal lives. Dayroom’s slow fade contained all of these ingredients. But while Woodstock ’99 was not the cause of Dayroom’s demise, we can point to it as the beginning of the end. The band continued to try for that big push, but a cloud now hung over such efforts, along with the feeling of laboring to get out from under a curse.

“The stakes for [Woodstock] were that we were expecting to be thrust into a much larger pool than we had been living in for the past eight-and-a-half years,” Mike says, “off eight dollars a day, living in a van, and sleeping on people’s floors pretty much every night. When we got to Woodstock we started to experience the real music business: where your heroes are no longer heroes; they’re real people and they can be blocking whatever you want to be.”

Riddle puts it more succinctly: “We were the bull and we missed the goddamned red cape…again. If anything, it was that recognition that we can try as much as we want, but this ‘Ain’t gonna happen, Dayroom!’ was bigger than us.”

There is more to the story, of course. Real life rarely follows tidy arcs. Not too long after the Woodstock debacle, Dayroom decamped to Europe for successive residencies in Paris and Madrid—a total of four weeks on the continent. Memories of the experience are mixed, tinged by contemporaneous financial struggles and (offscreen) domestic drama, but photos from that period reveal a lot of smiles, a lot of laughter. And the shows themselves appear to have gone well.

Later, for their big homecoming performance back in the States, Dayroom purchased a giant inflatable gorilla and mounted it atop the marquee at the Georgia Theatre. A grandiose, absurd, and costly gesture that apparently put one or two members in physical jeopardy, this event nevertheless joined the dozen or so iconic moments in Athens Music History. It’s impossible not to smile when pictures of the gorilla appear on social media. And it’s impossible not to marvel at the hunger and audacity of young bands. Would that we could all succumb to such a gentle madness from time to time.

And now we arrive full circle, at the apparent end of Dayroom in those final ringing notes in 2000, with the audience swarming the stage. But remember, real life doesn’t follow tidy arcs. The Dayroom legend, from fall 1991 to February 2000, is a complete tale with an origin, growing pains, trials by fire, eventual triumph, and decline. But for all the power and pathos of that final show, which occurred—appropriately—at a mental health benefit, it was not the last time Michael Winger sang “Cheap Wine” to a theater full of fans roaring it back at him. Not by a long shot. In truth, the door practically hit Dayroom in the ass on the way out, for they were back just one year later for a couple of reunion shows. And why not? Why arbitrarily prop up an impressive story arc when there is a chance to kick some more ass, have a good time, and pay some bills? That’s real life. Legends and real life can coexist. Both are, in a sense, true. They feed rather than negate each other.

Remember when R.E.M. broke up with the statement that they would never share a stage together again? How perfect and complete. How laudable.

And how disappointing and, frankly, depressing that they actually adhered to that promise.

Dayroom’s afterlife is more satisfying. Every several years, Mike, James (née Jimmy), Ryan, and Brad check in with each other and their fans for a handful of shows (most recently in summer 2023, including a standout performance at Athfest), and there is nothing cynical about the exercise. Everyone still likes each other. After all, no one got the chance to get corrupted by the music machine.

People travel from far-flung places. The 5-string bass gets dusted off. A lot of jumping ensues. Grown men yell “Yum yum!”

Did it really happen?

Yes. Mostly. When stories are retold many times, especially in the South, they expand to fit the needs of the teller, the listener, and the occasion. And when they’re set down on paper and adorned with descriptive detail, they expand even further.

For example: when Brad Zimmerman sat bolt upright in that sardine-can-tight apartment in Lawrence, were his bandmates all sleeping peacefully, with Winger’s drooling cheek pressed against an aquarium, or were they still awake, winding down after a long party?

Was it really an aquarium full of praying mantises? Or something else, like dung beetles?

Well, it depends. Which version works best around the campfire?

Acknowledgments

Many of the quotes from Michael Winger and Troy Aubrey in this piece derive from personal interviews (verbal and emailed) with the author. David Prasse, Ryan Kelly, and Brad Zimmerman provided additional background material via email and text. The quotes from James Riddle (along with additional quotes from Kelly, Winger, and Zimmerman) are taken from two as-yet-unreleased podcast recordings covering the Dayroom saga, as well as archival interviews from Dayroom’s heyday. Many many many thanks to Michael for providing access to the podcasts, and to Troy for compiling his comprehensive Dayroom archive of scanned media, without which much of the story of this wonderful band would have remained in the black hole of the pre-Internet 1990s.

Additional thanks to David Prasse and Slush Fund Recordings for commissioning this piece, and for allowing the author complete creative control of the outcome.